The Battle of Cesme, fought between the Russian and Ottoman navies on 6–7 July 1770, was a decisive engagement during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. It marked a significant Russian victory and showcased their growing naval strength. The Battle of Cesme remains a key historical event, symbolising the decline of Ottoman maritime power and the rise of Russia as a significant Mediterranean power.

The Battle of Cesme – Table of Contents

Background to the Battle of Cesme (1768–1770)

The Russo-Turkish War began in 1768, driven by Russian ambitions to weaken the Ottoman Empire and gain access to the Mediterranean. The Russians, led by Empress Catherine the Great, aimed to disrupt Ottoman control in the Aegean and support Greek uprisings against Ottoman rule. To achieve this, a Russian fleet under Count Alexei Orlov and Admiral Grigory Spiridov sailed from the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean via the Atlantic and Gibraltar.

In the early summer of 1770, the Russian fleet entered the Aegean Sea and engaged Ottoman forces. The Ottoman navy, commanded by Hüsameddin Pasha, anchored in the sheltered bay of Çeşme, near the western coast of modern-day Turkey. Though numerically superior, the Ottoman fleet was poorly organised and poorly trained compared to the Russian fleet.

The Ottoman Fleet

The Ottoman fleet was anchored in the Çeşme bay. It consisted of around 60 ships, including sixteen ships of the line, the Ottoman Navy’s largest vessels, armed with numerous cannons, though poorly manned and maintained. Additionally, there were six frigates (smaller, faster ships used for surveillance and support), six galleys (older warships with oars, still in use by the Ottomans and several smaller vessels, including transports and support ships. The flagship was the Real Mustafa, commanded by Hüsameddin Pasha; it was destroyed during the battle. While the Ottoman fleet was numerically superior, the ships were crowded in the confined bay, making them vulnerable to fireship attacks. Additionally, the crews lacked the training and discipline of their Russian counterparts.

Listed Ottoman ships in the Battle of Cesme:

| Ship | Class | Commander | Cannons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burc-i Zafer | Ship of Line | Admiral Hüsameddin Pasha | 86 |

| Hisn-i Bahri | Ship of Line | Rear Admiral (Patrona) Ali Bey | 84 |

| Ziver-i Bahri | Ship of Line | Vice Admiral (Riyâle) Cafer Bey | 84 |

| Mukaddeme-i Seref | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Semend-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Mesken-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Peleng-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Tilsim-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Ukaab-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Seyfi-i Bahri | Ship of Line | 70 | |

| Rhodos | 60 |

and Sinop, Turkey, Özdaş and Kızıldağ.

The Russian Fleet

The Russian fleet was smaller but better equipped and disciplined, consisting of nine ships of the line, three frigates, and several auxiliary ships, including fire ships. Admiral Grigory Spiridov commanded the fleet, and Count Alexei Orlov provided overall strategic direction. Key Russian ships included Sviatoi Evstafii (68 guns), Admiral Spiridov’s flagship at the outset of the battle, Svyatoslav (74 guns), and Tsesarevich (66 guns). Other powerful ships included Yevropa (66 guns), Tri Svyatitelya (66 guns), Rostislav (66 guns), Grom (50 guns), and Nadezhda (frigate). The Russians used fire ships, which were old vessels packed with explosives and set ablaze. These were decisive in destroying the tightly packed Ottoman fleet in the bay. Lieutenant Dimitri Ilyin, a Russian officer, commanded the successful fireship attack that turned the tide of the battle.

Listed Russian ships in the Battle of Cesme:

| Ship | Class | Commander | Cannons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sviatoi Evstafii Plakida | Ship of Line | Admiral A.G. Spiridov | 66 |

| Sviatoslav | Ship of Line | Rear Admiral Elphinston | 80 |

| Trekh Ierarkhov | Ship of Line | General Admiral Count A.G. Orlov | 66 |

| Evropa | Ship of Line | Commander Koleachoff | 66 |

| Trekh Sviatitelei | Ship of Line | Commander Gregg | 66 |

| Ianuarii | Ship of Line | Commander Bexasoff | 66 |

| Rotislav | Ship of Line | Commander Lupandin | 66 |

| Ne Tron Menia | Ship of Line | Commander Bezanchov | 66 |

| Saratov | Ship of Line | Commander Polivanoff | 66 |

| Nadezhda Blagopoluchiia | Frigate | Commander Steliphanoff | 34 |

| Afrika | Frigate | Captain Cleopin | 32 |

| Sviatoi Nikloai | Frigate | Commander Polikochin | 26 |

| Grom | Gunboat | 8 | |

| Severni Orel | Gunboat | Captain Sernchefnicov | 32 |

| Saint Paul | Transport Boat | Captain Sink | 14 |

| Kont Panin | Transport Boat | Captain Bodie | |

| Kont Orlov | Transport Boat | Captain Arnold | 16 |

| Kont Chemichev | Transport Boat | Captain Dishington | 22 |

| Pastellion | 16 |

and Sinop, Turkey, Özdaş and Kızıldağ.

6 July 1770: The First Engagement

In the morning, the Russian fleet positioned itself just outside the bay. The Russians sought to provoke the Ottomans into battle by initiating a bombardment. Admiral Grigory Spiridov ordered his ships to open fire, engaging the Ottoman fleet at long range. A fierce exchange of cannon fire occurred. In the afternoon, the Russian vessels advanced closer, engaging the Ottoman ships in an intense artillery exchange. The Ottoman flagship, Real Mustafa, became a key target.

The Sviatoi Evstafii Plakida (St. Eustathius Placidus), commanded by Admiral Spiridov, served as one of the lead ships of the Russian fleet during the battle. Early in the battle, the Sviatoi Evstafii engaged the Real Mustafa in a fierce artillery duel. This exchange was pivotal in the day’s battle, as both ships were heavily armed and served as flagships for their respective fleets. The Sviatoi Evstafii advanced aggressively, closing in on the Real Mustafa to deliver devastating broadsides. During the exchange, a Russian cannon shot struck the Ottoman flagship’s powder magazine, causing a massive explosion that destroyed the Real Mustafa, killing its commander, Hüsameddin Pasha, and most of its crew. The flagship’s destruction demoralised the Ottoman sailors, disrupting their coordination and leaving them vulnerable.

Due to its proximity, the Sviatoi Evstafii was caught in the blast of the exploding Real Mustafa. Flaming debris from the Ottoman flagship fell onto the Sviatoi Evstafii, igniting fires aboard the Russian ship. Despite efforts by the crew to extinguish the flames, the fire reached the ship’s powder magazine, resulting in a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the Sviatoi Evstafii. The explosion killed most of the crew of the Sviatoi Evstafii, though some survivors managed to escape by swimming or being rescued by nearby Russian ships. Admiral Spiridov, who had been aboard the Sviatoi Evstafii, managed to survive. He had transferred to the Tri Svyatitelya (making it the de facto flagship for the remainder of the campaign) shortly before the explosion, a move that saved his life.

As the day wore on, the remaining Ottoman ships retreated deeper into the Çeşme Bay for protection. The Russians refrained from pursuing them too closely, preferring to plan a decisive night attack rather than risk heavy losses in the confined bay. The Ottoman ships were crowded in a confined space, anchored in a defensive line, and believed the Russians would not attack at night, a fatal miscalculation. Their proximity to one another and lack of manoeuvrability made them highly vulnerable to fire or explosions.

7 July 1770: The Decisive Blow

The Russian commanders, Admiral Grigory Spiridov and Count Alexei Orlov, recognised the Ottoman fleet’s vulnerability. They prepared to launch fire ships, which were vessels loaded with combustibles, explosives, and tar. They were designed to ignite and cause chaos when steered into enemy ships.

During the night, the Russians launched a surprise fire ship attack, a tactic involving ships packed with explosives set adrift toward enemy vessels. The fire ships caused chaos, igniting the closely packed Ottoman fleet in the bay. Many Ottoman ships were destroyed or scuttled by their crews to prevent capture. The Russian fleet effectively annihilated the Ottoman navy with minimal Russian casualties.

Key Battle Tactics and Outcomes

Russian fireships were manned by small crews that ignited the ship and escaped in rowboats. The Ottoman fleet, anchored in a defensive position, relied on sheer numbers and the bay’s protection. However, their lack of manoeuvrability and the cramped anchorage made them easy targets. The Russian fireships caused catastrophic fires that spread quickly among the Ottoman ships, leading to their destruction or abandonment. The fires spread rapidly from ship to ship due to poor spacing, with explosions caused by the ignition of powder magazines adding to the destruction.

The battle resulted in the near-total destruction of the Ottoman fleet, with fifteen ships of the line, six frigates, and numerous smaller vessels destroyed. The Ottoman flagship Real Mustafa was among the first vessels destroyed. A direct hit caused its powder magazine to explode, killing the admiral and much of the crew. The Russian fleet emerged largely intact, achieving a decisive victory and demonstrating the effectiveness of fireship tactics in naval warfare.

Aftermath of the Battle of Cesme

The Ottomans suffered around 5,000 (11,000 by Russian sources) casualties, while Russian losses were around 640 casualties. The battle destroyed much of the Ottoman navy and showcased Russia’s growing dominance in naval warfare. The Russian victory at Çeşme encouraged uprisings in Greece, notably in the Peloponnese, Crete, and the Aegean islands and emboldened Russian territorial ambitions. It paved the way for the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774). It ended the war and granted Russia significant territorial and strategic advantages, including access to the Black Sea. It allowed Russian ships to navigate freely in Ottoman waters and influence Ottoman affairs on behalf of Orthodox Christians.

The Russian fleet‘s actions during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), particularly around the time of the Battle of Çeşme (1770), were closely tied to efforts to incite a Greek rebellion against Ottoman rule. This initiative, known as the Orlov Revolt, was part of Russia’s broader strategy to destabilize the Ottoman Empire by encouraging uprisings among its Christian subjects, particularly the Greeks. Russia presented itself as the protector of Orthodox Christians under Ottoman rule, a narrative used to gain support from the Greeks. Many Greeks were inspired by the idea of liberation and the potential restoration of a Greek Orthodox Byzantine Empire under Russian patronage.

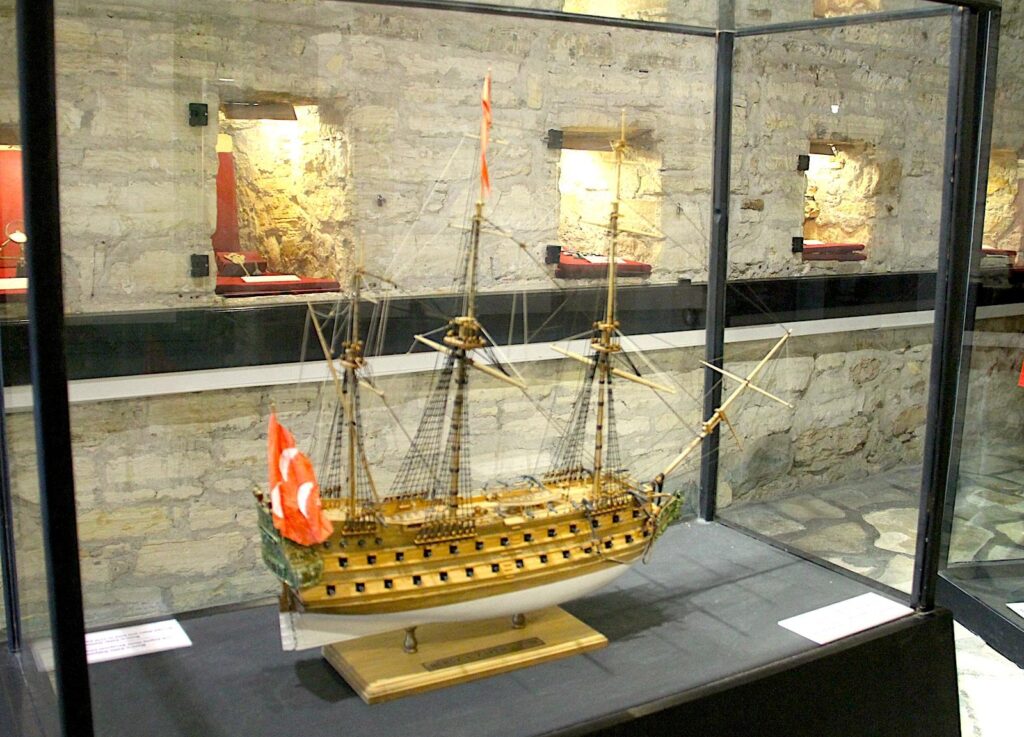

Condition of the Battle Site Wrecks

Documents in the Ottoman archives show that the Russians salvaged valuable material from the wrecks of the Ottoman fleet, and Greek and Turkish sailors looted the wreck sites. After the war, the Ottoman Sultan also ordered a salvage operation to recover the iron, cannon, and other materials from the wreck sites, enlisting divers from the islands of Kalymnos and Sömbeki. In a document from 1771, it is stated that there were about 50 intact cannons and a large number of metal pieces among the remains. The Sviatoi Evstafii has always been a focus of salvage operations since she was assumed to contain riches great enough to enable a voyage from Russia to the Aegean shores. Another reason for this focus was the Ottomans’ need for raw materials for ongoing war efforts. At least 200 marble cannonballs and more than 20 iron balls are displayed in the Çeşme Castle Museum. Consequently, little remains were found on the battlefield due to the ships being burned and blown up in the battle, salvages since then, damages by trawling activity and natural erosion and decay.

Recent Archaeology of the Battle Site

In 2016 and 2017, marine surveys were carried out in the naval battle sites in the Chios Strait, where the first engagement was fought. These surveys involved both side-scan sonar imaging and visual inspection by divers. The study area of the sites was determined with the aid of historical charts showing the lines of the fleets during the war. Eight North-to-South directed survey lines totalling a length of about 50 km parallel to the coastline were carried out between Alev Island and the Kaleyeri shallows at the Damlasuyu site in the Chios Strait.

After interpreting the sonar data, the targets were determined for visual verification by scuba dives during the second stage of the survey. The targets identified as the remains of a shipwreck were recorded by a video camera and 3D models were created. The data was integrated into the National Acoustic Database for Underwater Archaeological Sites of Turkey (NADUAST). During the inspections of the battlefield in the Chios Strait, where the first naval engagement was fought, two shipwreck sites, along with several anchors and cannons, were located in waters up to a depth of 60 metres.

During the diving inspection, partially buried and heavily damaged hull timbers, marble cannonballs, and some metal pieces were imaged at one site. The principal surviving part of the ship, which possibly belongs to the bow section, is approximately 7 metres long and 4 metres wide. The preserved end protrudes above the seabed by at least 1 metre at a depth of 15 metres. A large portion of the remains is covered by marine growth and in poor condition, causing uncertainty about the function of wooden elements and visible wooden components of the hull. Various ceramic pieces and a coffee cup fragment were found at the site, as well as 20 partly submerged marble cannonballs.

The second site in the battlefield, 600 metres north of the first wreck, are several small wooden fragments and metal findings, possibly from the rigging, scattered over 250 metres at a maximum depth of 45 metres. Very little of the hull remains were visible on the seabed. Three cannons made of iron, surrounded by concretions, were found, and a fourth bronze cannon with a Russian coat of arms was raised and earlier brought to Çeşme Castle Museum. A significant amount of the remains are likely still buried under the sediment. Rifle parts and flints, a sword, military uniform buttons, and silver and gold coins were raised from this site during a prior excavation and are now exhibited in the museum.

Exhibits in the Battle of Çeşme Hall in Çeşme Castle Museum recovered from battle shipwrecks (except the 1770 Russian Medal for Battle of Çeşme):

Due to severe damage caused by salvage operations carried out in various periods, as well as modern fishing activities and natural factors, it is difficult to determine the identity of the shipwrecks on the battlefield. However, both Ottoman and Russian archival documents and historical maps provide evidence that the Burc-i Zafer and Sviatoi Evstafii sank in the first stage of the Battle of Çeşme in the Chios Strait. The coins, cannons, and other artefacts recovered from the second wreck site during previous excavations were documented as belonging to a Russian warship, Sviatoi Evstafii. The archaeological findings, such as the coffee cup fragment, fire marks, and historical documentary research, suggest that the first wreck is the remains of the flagship Burc-i Zafer, and the lack of any other shipwreck in sonar data at the battle site supports this theory.

Social Media & Links

See also: LikeCesme.com – Cesme Castle Museum.

See also: Battle of Cesme 1770 – Ali Riza Isipek ISBN 9789944264273