An Ionian city, Metropolis (the city of the mother goddess) was established on the hill and slopes between the present day Yeniköy and Özbey neighbourhoods in the Torbalı District of İzmir. At an altitude of 142 metres, the Acropolis dominates the Torbalı Plain. Its strategical location relates to the geographical structure of Torbalı Plain at the western end of the Küçük Menderes (Kaystros) Basin between Bozdağlar (Tmolos) and Aydın Mountains (Messogis). The fertile agricultural lands are in the middle of the trade route connecting two important metropolises, the southern neighbour Ephesus and its northern neighbour Smyrna.

Location & Entry: Yeniköy, Sevgi Yolu Sk., 35860 Torbalı/İzmir. In the village of Yeniköy, 5km southwest of the city of Torbalı, 34km north of Ephesus, 130km southeast of Çeşme.– Open daily 08:00-17:30 (31 Oct- 1 Apr) 08:00-19:00 (1 Apr – 31 Oct) – Ticket price: Free entry.

Metropolis – Table of Contents

Brief History of Metropolis

Finds in and around Metropolis date settlements from the late Neolithic Age to the Middle Ages. Materials from excavations in 2004 at the Dedecik-Heybelitepe mound 2km south of the city indicate settlement in the late Neolithic-early Chalcolithic Age (5500-3200 B.C.) as well as early Bronze Age (3300-1200 B.C.) and one of the earliest settlements in the region. At Bademgediği Tepe, 7km north of Metropolis, excavations on the hill revealed a fortified settlement from the late Bronze Age with pottery corresponding to the 14th century B.C. Kingdom of Arzawa, and it might have been the Hittite city of Puranda.

The Greek geographer Strabo (64/63 B.C. – 24 A.D.) did not specify precisely the location of the city but wrote that there was a settlement between Smyrna-Ephesus, 120 stadions (120 x 150-210 metres) from Ephesus. The Greek mathematician Ptolemy (circa 100-170 A.D.) described Metropolis’s location as a city on the Ionian-Lydia border. The city was founded at the foot of the ancient Mount Gallesion (today as Mount Alaman). The region’s importance increased from the end of the 7th century B.C., as it controlled the main Ephesus-Smyrna road. Enclosed by a formidable wall, the Acropolis was built in the 3rd century B.C. and was enhanced in the 2nd century B.C. with the support of the Kingdom of Pergamon. With Roman domination in Anatolia, Metropolis continued to grow during the reign of emperors Augustus (63 B.C. – 14 A.D. Emperor 27 B.C. – 14 A.D.) and Tiberius (42 B.C. – 37 A.D. Emperor 14 B.C. – 37 A.D.) though was severely damaged in the earthquake of 17 A.D. There is evidence of repair and rearrangement of the city in the aftermath of the earthquake.

By the 2nd century A.D., Metropolis had a planned city identity with its sanctuary areas, public buildings, civil residences, and ordered streets despite being a city on the slope. A large bath and palaestra (ancient Greek wrestling school) complex was built in Metropolis during the time of Antoninus Pius (86 – 161 A.D. Emperor 138 – 161 A.D.), indicating the city’s importance at that time. The 3rd century A.D. was a problematic time for cities in the region, with severe earthquakes and Gothic raids.

Construction activities continued between the 4th and 6th century A.D. with smaller budgets and repair, renovation, and function changes to existing buildings were more prevalent. Nevertheless, the quantity of coins that date to this time suggests that economic prosperity in the city remained strong. The gradual bolstering of the Turkish territories in Anatolia made it crucial for the Byzantines to focus on building defence structures. The Byzantine Castle, built in Metropolis, whose strategic location was being challenged, was considerably strengthened during the 13th. Century A.D. The existence of a castle called Kızılhisar (red fort), in proximity to Torbalı, is mentioned in Ottoman sources. While this Byzantine castle continued briefly into the Ottoman Period, after the dominance was secured in the region, the settlement moved to Torbalı.

The latest Archaeological works on the ancient site began in 1989 and have been ongoing for over 30 years under the direction of Recep Meriç and Serdar Aybek. More than 11,000 historical artefacts consisting of ceramics, coins, glass, architectural pieces, figures, sculptures, metal, bone, and ivory artefacts. The artefacts are exhibited at the İzmir Archaeology Museum, the İzmir History & Art Museum and the Selçuk Ephesus Museum.

Hellenistic Theatre

Built on a natural hillside during the late Hellenistic period, the 8,000-10,000 capacity theatre experienced reconstructions during the Roman period, including adding a marble floor and enlargement of the stage building. The theatre, fashioned from marble, consists of segments for the orchestra, stage building, seating, and noble seats in the front row. These seats were reserved for clergy and emperors, are some of the best examples of Hellenistic marble work, and are backed by reliefs of Zeus’s lightning beam and Ares with a shield. The staircase edges are decorated with varying patterns of lion’s feet. The theatre hosted the city’s social, cultural, and artistic activities but lost its function in the 4th century A.D. Restored between 2000 and 2001, it can now seat approximately 4,000.

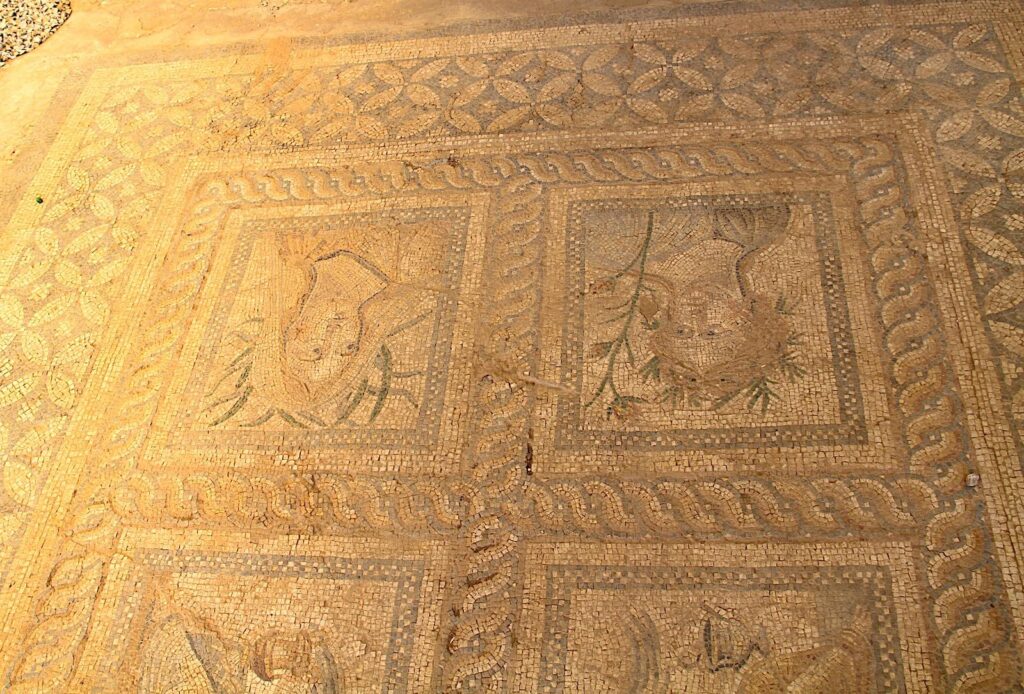

Mosaic Hall

The mosaic hall is the feast hall of a residence built in the 2nd century A.D. to the east of the perimeter wall of the Metropolis Theatre. It has some of the best examples of intricate floor mosaics found in Western Anatolia, with figures related to the theatre in a composition in two large frames. The first panel is coloured with tragedy and comedy masks, fish, birds and flowers associated with theatre plays and performers. The colouring creates a three-dimensional effect.

The content of the second panel includes four portraits placed at the corners of the rectangular frame. They may symbolise the personified four seasons. Spring is dressed in a blue-grey dress. His face is turned to the left, and he holds the flower branch with insects on it in his left hand as a sign of spring. The winter figure is personified as a woman whose head is covered with a mantle of leaves and branches of green grains embroidered in the background. A portrait in a red tunic personifies autumn. The mosaic panel has not preserved the image of summer. The four busts are separated by the figures of Eros in the centre, reclining on a kiln (bed). Two portraits facing each other in the scene lead to the interpretation that the figures may be Dionysus and Adriane, mythical characters identified with the theatre.

Acropolis & Fortress

Enclosed by a formidable wall, the Acropolis, built in the 3rd century B.C., covers an area of 16,000 square metres. The Metropolis Acropolis was formed by levelling the rocky ground to create a plateau, and the hill where the Acropolis is located is 145 meters above sea level. Overlooking the entire Torbalı Plain to the Menderes Plain, observing the entire environment to the most remote points was possible. The wall, made of empty blocks, is preserved at a height of up to three meters, especially in the north and south directions. The wall descended to the lower city in a zigzag form and was built large enough to embrace the whole city. The magnificent gate with two towers connects with the lower city. The walls have two gates located east and west. The main entrance in the east provides a connection with the lower city. The gate to the west opens to the cemetery (necropolis) area of the city, where the rock tombs are located. The Acropolis continued to exist throughout the Roman Period. The entrance of the new fortress, which was built in the city in the Middle Ages, was taken to the lower slopes of the city, but the civil settlement here was preserved by connecting the walls to the east gate of the Acropolis. Thus, two structures with a time difference of approximately 1,000 years continued to be used simultaneously.

The fortress on the slope below the Acropolis was built under the Hellenistic Laskaris dynasty during the early 13th century A.D., covering a smaller area than the Acropolis. The length of the front fortress is 110 metres, and the width is 42 meters. Its upper-level walls rest on the Hellenistic walls of the Acropolis, while its lower wall sits on the back wall of the Hellenistic Stoa. Large towers that still stand on the northern and southern corners were erected to ensure security in the lower section. The north tower, still with its battlements, is better preserved. The entrance to the front castle was provided through an arched door built on top of the Bouleuterion adjacent to the South Tower. The stairs built for the soldiers to climb the fortification walls are partially preserved. The construction of the fortress walls reused stones from Hellenistic structures surrounded by brick shards. In the towers of the front castle, columns, architraves, altars and even large-sized marble sculptures belonging to the Stoa and Bouleuterion were used on the walls as building materials.

Cisterns

During excavations in 2020, four water cisterns were discovered under 7 metres of soil inside the walls of the Acropolis that were built during the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. The cisterns built side-by-side are thought to have been built to provide water to the Acropolis in the event of a siege. It is estimated that the cisterns had a collective water capacity of 600 tons and could supply water to the settlement on the lower slopes of the Acropolis, including the upper bathhouse structure. The cisterns, approximately three floors tall, are the best-preserved monuments in Metropolis. Numerous food remains, animal bones, and ceramic pieces have also been discovered in and around the cisterns, and glazed ceramic pieces adorned with plant and animal figures make up most of the remains. It is believed the cisterns were converted into garbage dumps during the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Cult Place of Zeus Krezimos

During excavations in 2015, a cult site built for Zeus, the main god of Ancient Hellenistic mythology, was discovered in the ancient city. The site’s first and only centre of worship revealed that other beliefs also existed in the city, known as the city of the Mother Goddess. Further archaeological work unearthed findings related to religious ceremonies and rituals, including sections of columns with inscriptions, part of an altar and a pedestal. The presence of altars and possibly votive offerings suggests that personal and communal worship occurred here. Detailed work by the excavation team revealed that the area was a cult site dedicated to Zeus Krezimos, who was likely revered as a protector and benefactor of the city, and his cult played a central role in the religious identity of Metropolis.

The Peristillium House

The house was unearthed on the southern slope of the ancient theatre during excavations to explore the connection between the theatre and the city centre. It has a peristyle-style courtyard (columns supporting a porch roof surrounding the yard) and provides an understanding of civilian life during the Roman period. The central courtyard is large and covered with marble slabs, with four rows of columns surrounding it on each side. The vibrant wall plasters and rich findings in the spaces encompassing the courtyard indicate that the building belonged to a wealthy citizen.

Bouleuterion – Senate House

The 2nd century B.C. Metropolis Bouleuterion, the assembly house for the council of citizens, where decisions were made regarding the city administration, was the official city centre. The first archaeological studies to uncover the structure were conducted in 1998 and 1999. The Bouleuterion has a square plan structure with horseshoe-shaped rows of seating. It is 16.90 x 17.70 metres. The meeting room had a capacity of approximately 350 people, consisting of two compartments (kerkides) with radiant stairs. The circularly planned rows of seating are thought to have been on twelve rows, five of which have survived to the present day. In front of the sitting rows is a rectangular, elaborately crafted altar decorated with bull and ram heads and garland descriptions. Two cylinder-shaped altars dated to the period of the Roman Emperor Augustus were also found. The combination of Roman and original Hellenistic altars on the building floor indicates that the building was used for many years through several stages.

The south wall of the medieval fortress was built right on the middle stairs of the Bouleuterion. This fortification wall also divides the orchestra into two. Many columns, column headings, friezes, and sculptures were found on the wall during the excavations. The sculptures would have been located behind the cavea, in niches on the upper platform.

Stoa

Stoas were multifunctional buildings for religious ceremonies, political and philosophical meetings, and commercial and cultural events. The Metropolis Stoa, built in the 2nd century B.C., was supported by two rows of Doric columns. The names of the affluent individuals who financed the construction of the building are inscribed on the columns at the front. The stoa would have been a shaded area where council members could walk and discuss political, religious, philosophical, commercial and cultural issues. Those council members made the decisions about the city in the Bouleuterion. The stoa was excavated between 1989 and 1997. The terrace adjacent to the Bouleuterion (Assembly Building) offered a panoramic view overlooking the Torbalı Plain. The first construction phase was in the 3rd century B.C. In the 2nd century B.C., the length of the structure was extended to 67 metres, later vaulted shop structures were built under the east-facing ground of the Stoa. There were 19 columns in front supporting the wooden roof.

Upper Baths and Gymnasium

In antiquity, gymnasiums were public structures that provided physical and intellectual education to young people. According to a 2nd-century B.C. epigraph from Augustus, the Metropolis gymnasium was administered by Alexandra Morton. The Upper Bath complex was redeveloped after the disaster earthquake in 17 A.D., along with the gymnasium, which, over time, was integrated with the bath. With inscriptions found during the excavations carried out in Yukarı Hamam in 1997, it was revealed that wealthy people provided financial support for the construction of the bath. Four rooms with a pool were found at the bath entrance, which were later converted into apodyterium (dressing rooms) and are part of the gymnasium space. According to an inscription found, there is a preliminary bath section called probalanion (front hall), then the tepidarium (warm water bath) and caldarium (hot water bath) part of the baths. From here, the anointing-massage chamber called the aleipterion was entered. In the caldarium section of the bath, the bottom of the floor covering was a void to create high heat with a hypocaust system.

Latrines

In Roman times, latrines were divided into public and private and were built near or adjacent places such as an agora, baths, gymnasium, or a theatre. Apart from being used as toilets, they were also places for socialising. The Metropolis latrines were integrated into the southeastern corner of the upper bath at the end of the 2nd century A.D. They measured 11.5 x 5.75 metres and served the visitors to the baths and the people in the city centre. The floor of the latrine is covered with square bricks, and the clean water channel carved in marble is preserved. It is thought that the seats were made of wood. A small limestone basin was found in situ in the centre of the building. People coming to the latrine would drop the xylospongium (stick with a sponge tied to the end) into this basin. The latrine was thought to be used until the end of the 3rd century A.D.

The Atrium House

The first-century A.D. Atrium House is located on the lower terrace of the Upper Bath and Gymnasium structure. Its façade faces east, benefiting from daylight and heat; the west side of the building leans on the flattened bedrock. The house is different from other house plans seen in Western Anatolia. The entrance to the house is provided by a marble door sill from the south side; such spaces usually have walls with brick floors and flat plaster. While simpler than other residences in the city, the mosaics on its floor are unusual to Metropolis, the inscriptions “Agathe Tykhe “, meaning “Good luck” in Greek, and “Bona Fortuna” meaning “Good luck” in Latin. In the middle of these inscriptions is a black and white panel decorated with geometric motifs and a large kantharos (ritual cup) motif in the middle.

Lower Bath-Palaestra

The Lower Bath-Palaestra was a Roman Imperial Period bath building with a marble-clad interior facade. Specially designed stepped pools are located on the sides of the central hall. Built where the slope settlement of the city meets the plain, the Lower Roman Bath-Palaestra is one of the most important structures of the Roman period Metropolis. The building had an area of approximately 6,000 square meters, indicating that the city expanded in population and area during the Roman Period. Studies on Lower Bath-Palaestra, which started in 2003, showed it was built on a smaller scale in the 1st century A.D. in the period of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD); it was enlarged to the current plan. The building complex was converted into small workshops in the Middle Ages.

Archaeological works were completed between 2009 and 2014 in the frigidarium (cold room), tepidarium (warm room), and caldarium (hot room) washing pools, which form the main parts of the bath, and the geometric ornament mosaics surrounding the 40 x 40 metres of the palaestra. Between 2015 and 2019, archaeological works were done on the service corridor and the well-preserved northern mosaic hall.

Social Media

Ministry of Culture & Tourism – Metropolis Archaeological Site English Website – Includes link to brochure.

Turkish Museums – İzmir Metropolis Archaeological Site English Website

İzmir Provincial Directorate of Culture & Tourism – Metropolis (Torbalı) English Website

Sabanci Foundation – Metropolis Archeological Excavations English Website

Metropolis Excavation Presidency – Metropolıs Excavation / Research Turkish Website