Ephesus, near Selçuk 160km southeast of Çeşme, is one of the most well-preserved ancient cities in the Mediterranean region; as a UNESCO World Heritage site, it attracts millions of tourists annually who come to explore its rich historical and cultural heritage within what was once the estuary of the river Kaystros, a continuous and complex settlement history can be traced in Ephesus from the 7th millennium B.C. at Cukurici Mound until the present at Selçuk. It was subject to continuous shifting of the shoreline from east to west due to sedimentation, which led to several relocations of the city site and its harbours.

Getting there: 3km west of the centre of Selçuk and 160km southeast of Çeşme via the E87 highway and D550 hour drive by car via İzmir and Belevi.

For transport, advance tickets and guided tours from Çeşme, Alaçatı, and other locations to Ephesus Ancient City, and the House of Mary, see Get Your Guide, who present various options – click here for details, prices and reservations.

Ephesus Ancient City – Table of Contents

Brief History of Ephesus

The area around Ephesus was inhabited as early as 6000 B.C., during the Neolithic period; by the Bronze Age, around 1500 B.C., Ephesus was a thriving settlement associated with the Mycenaean civilization. The Neolithic settlement of Cukurici Mound, marking the southern edge of the former estuary, is now well inland and was abandoned before settlement on the Ayasuluk Hill from the Middle Bronze Age. Founded before the 2nd millennium B.C., the sanctuary of the Ephesian Artemis, originally an Anatolian mother goddess, became one of the ancient world’s largest and most powerful sanctuaries. Around 1000 B.C., Greek colonists, primarily Ionians, established the city of Ephesus around Artemision. The Ionian cities that grew up in the wake of the Ionian migrations joined a confederacy under the leadership of Ephesus. Ephesus came under Lydian control in the 7th century B.C. under King Croesus (reign 585-546 B.C.), who contributed significantly to the city’s wealth and the Temple of Artemis. In 547 B.C., Ephesus was conquered by the Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great (reign 550-530 B.C.)

Ephesus was liberated by Alexander the Great in 334 B.C., leading to a period of prosperity and Hellenistic influence. Around 281 B.C., Lysimachos, one of the twelve generals of Alexander, later the King of Thrace (reign 306-281 B.C.), founded the new fortified city of Ephesus while leaving the old city around the Artemision. When Asia Minor was incorporated into the Roman Empire in 133 B.C., Ephesus was designated as the capital of the new province of Asia. By the 1st century A.D., Ephesus was one of the largest cities in the Roman Empire, known for its grand architecture, including the Library of Celsus and the Great Theatre. Ephesus is notable in early Christian history, mentioned in the New Testament, and was the site of the third ecumenical council in 431 A.D. The city began to decline in importance during the Byzantine era due to the silting up of its harbour, which hindered trade. Ephesus suffered from Arab raids in the 7th and 8th centuries, further contributing to its decline. When the region came under Ottoman control in the 14th century, Ephesus was largely abandoned, and its ruins became a quarry for building materials.

Over the past 150 years, excavations and conservation have revealed grand monuments of the Roman Imperial period lining the old processional way through the ancient city, including the Library of Celsus and terrace houses. Little remains of the famous Temple of Artemis, one of the ‘seven wonders of the world’ which drew pilgrims from all around the Mediterranean until it was eclipsed by Christian pilgrimage to the Church of Mary and the Basilica of St. John in the 5th century A.D. Pilgrimage to Ephesus outlasted the city and continues today. The Mosque of Isa Bey and the medieval settlement on Ayasuluk Hill mark the advent of the Selçuk and Ottoman Turks.

EPHESUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

Map location & entry: Atatürk, Efes Harabeleri, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir. – Open daily 08:00-00:00 – Ticket price as of July 2024 – €40 (including entrance to Ephesus Experience Museum). Combined ticket including Main Archaeological Site, Ephesus Experience Museum, The Terrace Houses, Ephesus Museum (Selçuk) and the Basilica of St. John (Selçuk) as of July 2024 is €65.

Entrances

Entry to The Ancient City of Ephesus is through either of two main entrances: the Lower Gate off the D515, closer to the town of Selçuk, the Church of Mary and the ancient harbour area, or the Upper Gate, off the D550, close to the Baths of Varius and State Agora. If transportation allows, many visitors prefer to enter through the Upper Gate and exit through the Lower Gate to take advantage of the less strenuous downhill walk. Shuttle services and taxis frequently operate between the two gates, allowing visitors to tour the site without backtracking. The entrance areas include parking, ticket booths, visitor information centres, restrooms, tour guides, and souvenir shops. Arriving early in the morning can help avoid the peak tourist crowds and the midday heat, especially during summer. It is advisable to bring water, wear comfortable walking shoes, and use sun protection, as the site covers a large area and involves considerable walking.

Kouretes Street

Kouretes (or Curetes) Street is one of the three principal streets of Ephesus, stretching between the Hercules Gate and the Library of Celsus. It was an archaic ceremonial and sacred route leading to the Temple of Artemis, and it was named after the priests who walked the street during religious rituals. The Kouretes (Curetes) were semi-deities in Greek mythology and a class of priests and priestesses in Ephesus that started as a cult of six priests (later expanded to nine) that re-enacted the birth of the goddess Artemis. Kouretes referred to priests from the cult of Artemis, but the Romans extended the name to priestesses of Hestia, who were trusted with the sacred fire housed in the Prytaneion that represented the heart of Ephesus.

Laid down in Hellenistic times, the street cuts diagonally across the grid system. Along the street were numerous fountains, monuments, and statues. The residences on the slope housed the wealthiest Ephesians, and under their properties were collonaded galleries and shops with mosaic-tiled floors. The buildings along the street were damaged in many of Ephesus’s earthquakes and were often repaired using materials recycled from other collapsed structures. Differences in design are apparent on the columns today from the reconstructions after a 4th-century earthquake.

Major sites on Kouretes Street (From the top entrance gate to Marble Road):

-

(i) Baths of Varius

-

(ii) State Agora

-

(iii) Isis Temple

-

(iv) Odeon (Bouleuterion)

-

(v) Temple of Domitian

-

(vi) Memmius Monument

-

(vii) Pollio Fountain

-

(viii) Heracles Gate

-

(ix) Hadrian’s Temple

-

(x) Scholastica Baths

-

(xi) Fountain of Trajan

-

(xii) Terrace Houses

-

(xiii) Latrines

-

(xiv) Brothel

Marble Road

The street that circles Mount Pion (Panayır) was the thoroughfare and considered the sacred way of Ephesus. The segment between the Library of Celsus and the Commercial Agora was covered with marble plates. The original construction dates to the 1st century A.D., though it was rebuilt in the 5th century A.D.

The marble section of this sacred road was used by carriages only, and the tracks of chariot wheels can still be seen. The Commercial Agora bounded the western side, and the columns’ remains stand on a base wall 1.7 metres high. This wall and the stairs on the north and south ends of the Agora were erected for pedestrians during the reign of Nero (37-68 A.D., reign 54-68 A.D). Statues of important people would have been placed along the road, and notices from the emperor carved into stone blocks.

Major sites on Marble Street (from Kouretes Street to The Arcadiane):

-

(xv) Library of Celsus

-

(xvi) Commercial Agora

-

(xvii) Gate of Mazeus and Mithridates

-

(xviii) Great Theatre of Ephesus

The Arcadiane (Harbour Street)

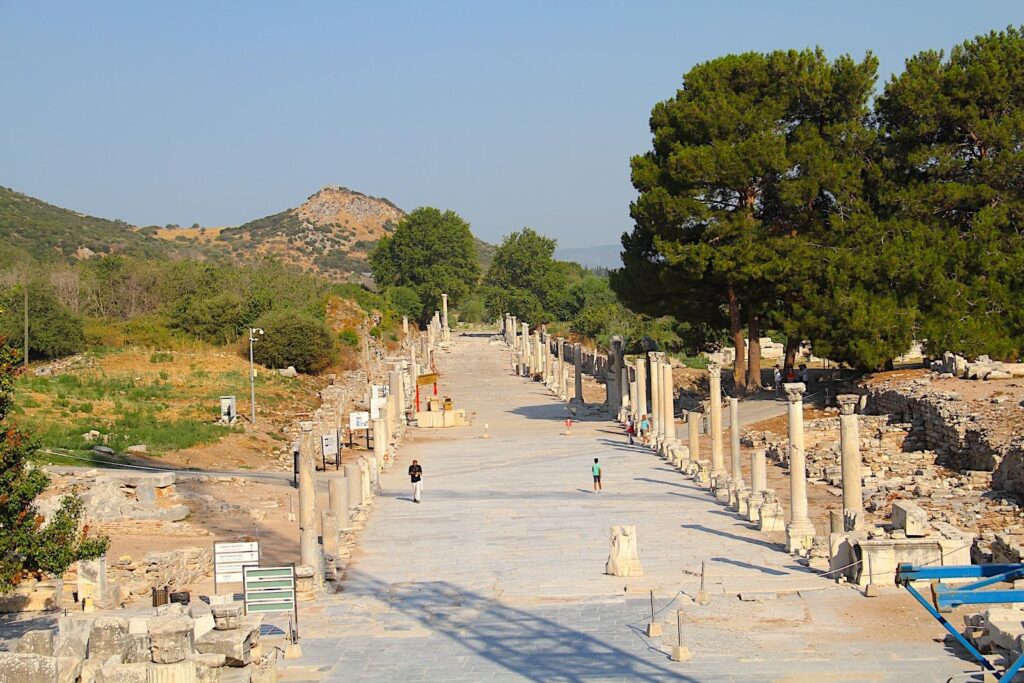

Arcadiane Street (also known as Harbour Street) is a collonaded road named after Emperor Arcadius (377-408 A.D., reign 395-408 A.D.); however, the street probably dates to an earlier Hellenistic period before the 1st century B.C. Fragments and foundations of the Harbour Gate, located on the axis of the road at its western end, indicate that Arcadius rebuilt and raised the level of the earlier road after a series of earthquakes. The street has a width of 11 metres and is well preserved over its 500-metre length, starting at the theatre and ending near the ancient harbour. Monumental gates with three passageways in the form of triumphal arches were at each end of the street, though the gate near the theatre was destroyed.

The pavements on each side of the road have a width of 5 metres, and the Corinthian order porticoes would have been covered with mosaics. Behind the shaded and sheltered arcades were various shops. Sewage channels ran underneath the marble flagstones of the street. Writings note that roads had street lighting, as stated by the Roman historian Ammianus (circa 330-391/400 A.D.): “The brilliancy of the lamps at night often equalled the light of day”. An inscription exposed during the street excavations ratifies this claim. It states that fifty lamps illuminated Harbour Street at night, an exceptional luxury in Roman times, affirming the city’s affluence.

Major sites on/near The Arcadiane (from Marble Road to the Harbour):

-

(xix) Vedius Gymnasium and Baths

-

(xx) Access to the Church of Mary

-

(xxi) Ancient Harbour and Habour Baths

(i) Baths of Varius

On entering the upper (south) entrance gate of Ephesus Archaeological Site, directly ahead is a marble structure identified as the Baths of Varius, one of four sets of baths in the city. Commissioned by Titus Flavius Damianus, a notable figure from Ephesus in the 2nd century A.D., the baths included a private room for him and his wife. They are constructed with stone blocks and supported on the north and east at a depth of 6-7 metres cut into the hillside rock. Laid out in a classic Roman bath configuration, with the caldarium (hot rooms), the tepidarium (warm rooms) and the frigidarium (cold rooms). The baths were remodelled on multiple occasions, and in the 5th century A.D., Byzantine influences are evident in the interior decoration, including mosaics that cover a 40-metre corridor.

(ii) State Agora and (iii) Isis Temple

The State Agora in Ephesus was the heart of the ancient city and was primarily used for political, administrative, and commercial activities, being the central gathering place for public affairs. The Agora also facilitated economic activities, with merchants and traders setting up stalls and shops around the square. The original construction dates back to the late Hellenistic period, the 1st century B.C., but it saw significant renovations and expansions during the Roman period. The Agora was a large open square surrounded by stoas (covered walkways) and various administrative buildings, measuring approximately 160 x 73 meters, making it one of the largest agoras in the ancient world. Key structures within and around the Agora included the Prytaneion (city hall), the Bouleuterion (council house), and the Basilica.

The Temple of Isis in Ephesus highlights the city’s cultural and religious diversity during the Roman period. The Temple was dedicated to Isis, the Egyptian goddess of fertility, motherhood, and magic, reflecting Egyptian religious practices in Ephesus, constructed during the Roman era, likely in the 2nd century A.D., when the worship of Isis spread throughout the Roman Empire. It featured a central cella (inner chamber) and an outer colonnade of 10 x 6 columns, with altars and statues dedicated to the goddess. On the Temple’s façade were statues depicting the legend of Odysseus and Polyphemos, now displayed in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum.

Today, the ruins of the State Agora include the foundations of buildings and portions of the stoas, offering a glimpse into its historical grandeur. The remains of the Temple of Isis are more fragmented, but ongoing archaeological efforts continue to reveal details about its structure and significance. Both the State Agora and the Isis Temple underscore the historical importance of Ephesus as a major centre of political, economic, and religious life in the ancient world.

(iv) Odeon (Bouleuterion)

The Odeon, also known as the Bouleuterion, was a multifunctional building serving both as a council house and a small theatre. It was built circa 150 A.D. and commissioned by the wealthy Ephesians Publius Vedius Antoninus and his wife, Flavia Papiana. Today, the remains of the Odeon are well-preserved compared to many ancient structures. The seating area (cavea), circular space in front of the seats (orchestra), and parts of the stage building are still visible.

The structure is a semicircular building resembling a small theatre, combining elements typical of a council house and a performance venue, seating approximately 1,400 spectators. The cavea is arranged in a semicircle with tiers of marble benches, divided into two sections by a horizontal walkway (diazoma), providing efficient access for spectators. The orchestra was used for performances and as the area where council members could sit during meetings. The stage building was elaborately decorated with columns, niches, and statues, showcasing the architectural and artistic grandeur typical of Roman theatres. Unlike many larger theatres, the Odeon probably had a wooden roof, which would have provided better acoustics and protection from the elements, making it suitable for year-round use.

(v) Temple of Domitian

The Temple of Domitian was constructed during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81-96 A.D.) and was one of the first structures in Ephesus dedicated to a Roman emperor, reflecting the city’s strong ties to the Roman Empire. While the temple was dedicated to Domitian, after his assassination and the subsequent condemnation of his memory, the dedication shifted to the Sebastos (Roman Augustus) imperial dynasty, and the temple continued to be a significant ceremonial site within Ephesus. It was a large and imposing structure, built on a raised terrace substructure 50 x 100 metres, creating a sense of elevation and grandeur reflecting Roman architectural styles infused with local elements. A peripteral structure surrounded by a single row of columns likely had a rectangular floor plan typical of Roman temples, with a portico and a cella (inner chamber). Constructed using locally sourced materials, including marble, the 24 x 37-metre temple featured rich decorative elements, including friezes and reliefs depicting various deities and mythological scenes. In the temple stood a 5-metre-high cult statue of the emperor, of which only the head and one hand remained; these are exhibited in the archaeological museum in Selcuk. Archaeologists have uncovered significant parts of the temple’s foundation and fragments of its decorative elements, allowing for reconstructions of its appearance. Today, the foundation and some column fragments are visible, providing insights into the temple’s original splendour and its role within the urban landscape of ancient Ephesus.

(vi) Memmius Monument

The Memmius Monument on Kouretes Street was erected in the 1st century B.C. in honour of Gaius Memmius, a Roman senator commemorating his family’s contributions to the city and the Roman state. Gaius Memmius, born circa 70 B.C., was appointed suffect consul (the highest elected public official) in 34 B.C. and proconsular governor of Asia sometime after 30 B.C. Gaius Memmius was the son of politician and poet Gaius Memmius (circa 99-49 B.C.), and his mother was Fausta Cornelia (born circa 88 B.C.), the daughter of notorious Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 B.C.), dictator of Rome. The monument was originally a triumphal arch or a tower-like structure with steps leading to a base platform. Though many have been eroded, the square base has reliefs and inscriptions depicting various historical and mythological scenes. The monument symbolised Roman authority and influence in Ephesus and the city’s loyalty to Rome.

(vii) Pollio Fountain

The ornate marble Pollio Fountain near the eastern end of Curetes Street was a practical source of fresh water and a monument of artistic and cultural significance. Built around 97 A.D., it was commissioned by C. Sextilius Pollio, a Roman politician, honouring his family and contributions to the city, such as building the aqueducts that carried water to the city’s fountains from up to 42km away. The fountain, strategically placed in a prominent and frequented area, was designed in a typical Roman nymphaeum style, characterized by its elaborate decoration and multiple water outlets. The façade of the fountain was richly decorated with niches, statues, and reliefs. The central niche likely housed a statue of Pollio or a deity; other niches contained statues, including one of the Head of Zeus and a themed group depicting the adventures of Odysseus excavated from the fountain basin. Relatively large for a fountain, it included a large rectangular basin to collect and distribute the water fed by the city’s aqueduct system, ensuring a continuous water flow. Today, the Pollio Fountain has some of its original structure and decorations still visible, including the basin, a high arch facing the temple of Domitian and parts of the façade preserved. Some statues and reliefs are displayed in the Ephesus and Istanbul Archaeological Museums; others are housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the British Museum in London.

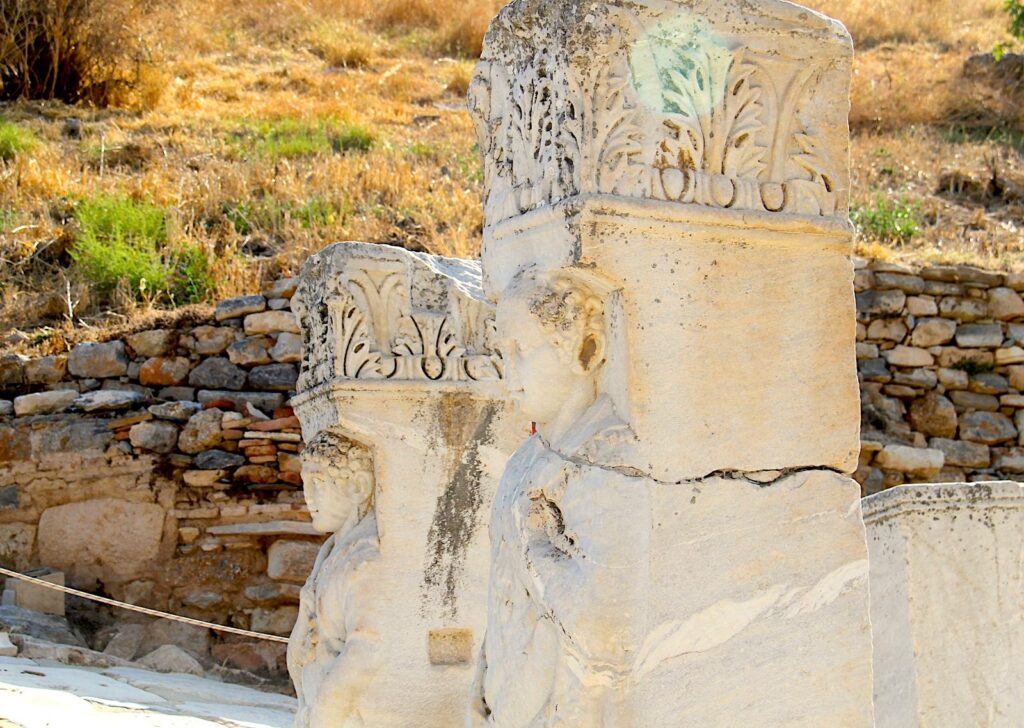

(viii) Heracles Gate

The Heracles Gate dates to the 4th century A.D., the late Roman period. Initially, the gate served as a ceremonial entrance, marking a significant point on the processional route through the city, and later functioned as a defensive structure. Named after Heracles (Hercules), the legendary Greek hero, due to the prominent reliefs on the gate’s pillars. Heracles is shown wearing the skin of the Nemean lion, a symbol of his strength and heroism. The reliefs are carved in high relief, showing detailed workmanship that highlights the muscular form and heroic posture of Heracles. These carvings are among the best-preserved artworks in Ephesus. The gate consists of two massive pillars with decorative reliefs, which initially was part of a more extensive archway structure, and the two-story building would have had six columns on each floor. Although many have not survived, the gate likely included other decorative elements, such as inscriptions and additional carvings. The narrow passage created by the gate helped control the flow of people and vehicles along Curetes Street. Today, the Heracles Gate stands partially restored. The reliefs of Heracles are still visible, although weathering and time have worn down some of the finer details.

(ix) Hadrian’s Temple

The Temple of Hadrian in Ephesus was built in the 2nd century A.D. to honour Emperor Hadrian (76-138 A.D., reign 117-138 A.D.) during his lifetime, a testament to his influence and the respect he commanded across the Roman Empire. The temple stands before the Scholastica Baths, facing Kouretes Street. Construction of the temple likely began around 130 A.D., coinciding with Hadrian’s visit to Ephesus. The temple’s construction was part of a larger pattern of urban development and imperial patronage that characterized Hadrian’s reign, commissioning numerous structures across the empire, including the Pantheon in Rome and Hadrian’s Wall in Britain. The Temple of Hadrian, like many ancient structures, underwent modifications and repairs over the centuries. In the 4th century A.D., during the reign of Emperor Theodosius, some changes were made to the temple, possibly adapting it for new uses as the city transitioned into the Christian era. The temple was ruined on an unknown date, and its blocks were reclaimed to erect the retaining wall in the middle of Kouretes Street.

The temple was uncovered in 1956 and re-erected in 1957/8. It has undergone restoration to preserve its elaborate carvings and structural integrity. It is a fine example of Roman architecture, specifically in the Corinthian order; the columns are characterized by ornate capitals decorated with acanthus leaves. The temple’s facade is its most striking feature, comprising four columns supporting a curved architrave with an intricate relief of Tyche, the goddess of fortune. This architrave is not flat but curved, which is relatively unique among Roman temples. The temple is adorned with rich friezes and reliefs, and a notable feature is the frieze depicting the mythological foundation of Ephesus. These reliefs include scenes with Androklos, the city’s founder, and other mythological figures and deities now housed in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum. It measures about 7 x 10 meters and sits on a raised platform, typical of Roman temple design. The temple features a small portico at the front, where the four columns support the ornate architrave. This portico creates a small but significant entryway emphasising the temple’s sacred nature. The 5.0 x 7.5 metre inner chamber (cella) of the temple would have housed a statue of Hadrian, along with other possible dedications to gods and emperors. The cella is accessed through a single door, and while relatively small in comparison to other grand Roman temples, it was richly decorated. The temple was constructed primarily from local marble, prized for its quality and beauty.

(x) Scholastica Baths

While the Scholastica Baths in Ephesus were initially constructed in the 1st century A.D., they are named after an affluent 4th century A.D. Christian woman, Scholastica, who financed their renovation. Public baths were central to Roman social and cultural life, serving as places for bathing, socializing, and conducting business. In the 4th century A.D., the baths underwent substantial renovation funded by Scholastica, reflecting the continued importance of the baths in the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. The renovations likely included updates to the heating system, water supply, and decorative elements. Constructed in the typical Roman architectural style, they feature a series of interconnected rooms with functions related to the bathing process and showcasing the Romans’ advanced engineering skills, particularly in water management and heating systems.

This bath complex, the largest in Ephesus, includes several key components. The first is the apodyterium (changing room). Visitors enter the apodyterium first to change clothes and store their belongings in niches along the walls. Frigidarium (Cold Room): A cool room with a cold-water pool. Bathers cool down after the hot baths. Tepidarium (Warm Room): Kept at a moderate temperature, serving as a transition space between the cold and hot rooms. Caldarium (Hot Room): The hottest room in the bath complex, featuring a hot-water pool and steam. Sudatorium (Sweating Room): Like a modern sauna, the sudatorium was a steam room where bathers could sweat out impurities. The baths were heated by a hypocaust system (underfloor heating) using raised floors on pillars to create a space for hot air to circulate, heating the floors and walls, with furnaces (praefurnia) outside the bath complex to generate the hot air. Hot water was supplied by nearby boilers. Aqueducts and pipes supplied water to the pools and bathing rooms. Wastewater was managed through an efficient drainage system.

The baths would have had three stories and three entrances, two of which would have been public access leading onto Kouretes Street and a side street. The upper two stories have collapsed, and only the ground floor and the arch of the third floor can be seen. The Scholastica Baths were adorned with mosaics, marble, and statues, reflecting the wealth and artistic tastes of Ephesus’ inhabitants. A headless statue of Scholastica stands at the eastern entrance of the baths. The complex likely included other facilities such as gyms, gardens, and libraries, further emphasizing its role as a centre of public life. The Scholastica Baths have been partially excavated and restored, providing valuable insights into Roman bath architecture and urban life in Ephesus.

(xi) Fountain of Trajan

The Fountain of Trajan was built during the height of the Roman Empire around 104 A.D. in honour of the Roman Emperor Trajan (53-117 A.D., reign 98-117 A.D.) and his contributions to the city and the empire. The fountain’s facade is elaborately decorated and was originally two stories high. The lower story is characterized by a series of arches and columns, and the upper story likely featured additional decorative elements and niches. A significant feature of the fountain was a large statue of Emperor Trajan, which stood prominently within the structure, depicting the emperor in a heroic pose, emphasizing his power and divine favour. The statue’s base, which remains today, shows Trajan with his foot on a globe, symbolizing his dominion over the world. The reliefs and inscriptions celebrated Trajan’s achievements and the prosperity of Ephesus.

The fountain had two ornamental pools, one in the front and one at the rear. It was constructed primarily from local marble, adding to the fountain’s aesthetic appeal and demonstrating the wealth and importance of Ephesus. The fountain’s structure was grand, with a height of around 12 meters and a width of about 20 meters. The large basin at the fountain’s base provided a functional water source for the city’s inhabitants and a decorative feature. Water flowed from the fountain into a large basin, creating a visually and acoustically pleasing environment. The use of water in Roman fountains was both practical and symbolic, representing life, abundance, and the emperor’s benevolence. The Fountain of Trajan has been partially restored at the site, while fragments of the partially restored statue of Emperor Trajan, including the globe, are on display in the Ephesus Archaeological Museum in Selçuk alongside reliefs and inscriptions.

(xii) The Terrace Houses

NB: While the Terrace Houses are part of the Ephesus Archaeological Site, there is an additional charge for access to the Terrace Houses.

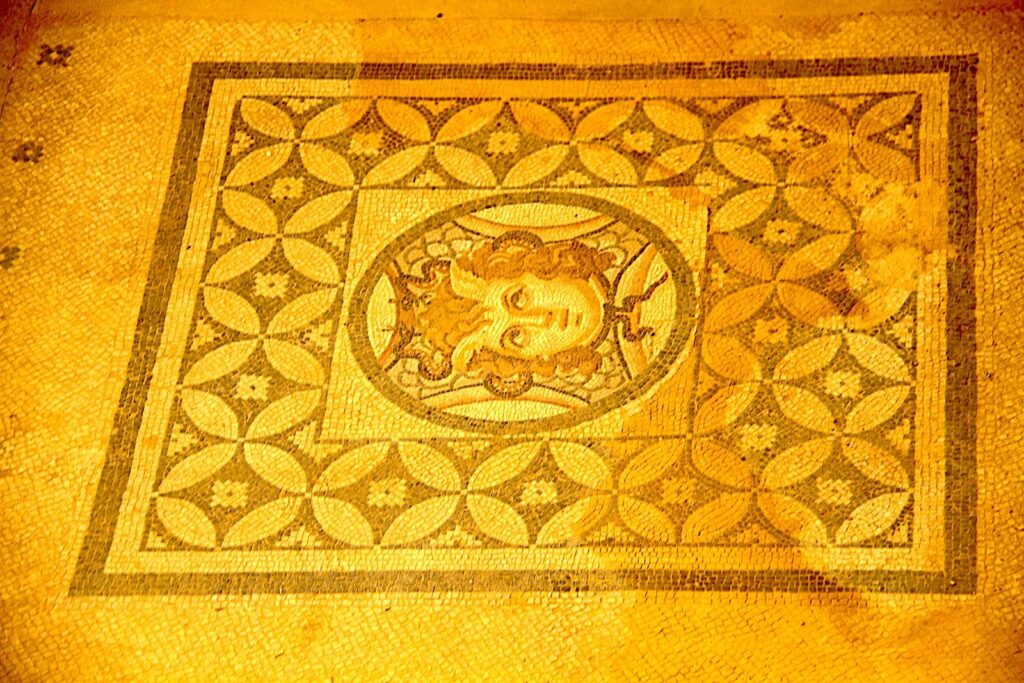

The Terrace Houses complex in Ephesus consists of upper-class residential villas situated on the hill on Kouretes Street close to Hadrian’s Temple and the Library of Celsus. Since 1960, two (east and west) housing developments have been unearthed; restoration continues today, and the entire area is covered with a protective roof. Wall paintings and drawings illuminate the inhabitant’s lives and interests, showing illustrations of gladiators, cartoons, and animals. Graffiti includes references to people’s names, poems, statements of love and lists of goods and activities with prices.

Before the Roman terrace houses, between the 6th and 4th century B.C., the area on the slope was a graveyard. Later, during the Hellenistic period, around 200 B.C., the three terraces were established using immense stone walls. Before the 1st century B.C., on the north terrace was a house, while a crafts area developed along the other terrace areas.

The private housing development on the east side covers approximately 2,500 square metres over three terraces dating back to the 1st century A.D. and was occupied and updated through to the 7th century A.D. This eastern complex includes a domus (Roman luxury townhouse) on the second terrace and other middle-class residences, each with running water and separate street entrances. The peristyle courtyard encircled with Ionic colonnades, a hall, a dining room, and a private basilica of the Domus has been preserved. Built at the beginning of the 1st century A.D., the Domus was improved circa 300 A.D., with the addition of thin-coloured marble revetments to the wall in the southern part of the courtyard.

The housing development on the east side includes at least five well-preserved luxury villas with inner courtyards. Several rooms are adorned with frescoes and artworks, and this complex has Western Türkiye’s largest collection of Roman period mosaic floors. dating from the early 1st century to the early 3rd century A.D. The mosaics are predominantly geometric patterns with small black and white stones like those found in Italy. In contrast, a few others are multi-coloured mosaics depicting a lion and the figures of Dionysus, Medusa, Nereids, and Triton.

In the west complex is a 900 square metre two-storey peristyle house, originally from the 1st century A.D., updated in the 2nd century A.D. Among 12 ground floor rooms is a vestibule, hall, kitchen, and bathroom with bathtub. Besides floor mosaics, this house has wall frescoes depicting floral motives, a peacock and figures of Ariadne, Eros, and Herakles. Other houses include a 1st-century A.D. villa that features frescoes depicting two Eros figures and illustrations of birds, a mosaic with Nereids and a glass mosaic covering the vault of a niche. A house with frescoes characterising Apollo and the Muses, dated circa 450 A.D. A house in the northeastern corner of the complex was uncovered with a very well-conserved fresco portraying the seated Socrates, now on display in the Ephesus Museum in Selçuk.

(xiii) The Latrines

The public latrines at Ephesus, located close to key structures such as the Hadrian Temple and the Celsus Library, are a notable example of engineering and urban planning, highlighting the advanced sanitation practices of the ancient Roman world. Built in the 1st century A.D., intended for communal use, they were part of the broader infrastructure improvements to accommodate the growing population and the increasing number of visitors to the city. These facilities served practical needs and acted as social hubs where people could engage in conversation and business. The latrines were built as a rectangular room with an open central courtyard. Stone benches with keyhole-shaped openings ran along the walls on three sides of the room, seating multiple users simultaneously. Beneath the benches, a deep drainage channel carried waste away, connected to the city’s sophisticated sewer system. Fresh water constantly flowed through a channel at the users’ feet, which could be used to clean themselves with a tersorium (a sponge on a stick). The walls and floors of the latrines were decorated with marble and mosaics, reflecting the Roman emphasis on aesthetics even in utilitarian spaces. The roof, supported by columns, provided shelter from the elements, making the latrines comfortable to use in various weather conditions.

(xiv) The Brothel

One of the most celebrated carvings along Marble Street at the intersection of Kouretes Street is assumed to be an advertisement for a brothel and could be the earliest commercial advert in history. The block is a carving of a left footprint, a purse of money, a woman, a heart, and a library. This has been construed as saying that a visitor could continue walking that way to find a brothel on the left side of the street. Anyone whose foot was smaller than the one on the pavement would have been declared underage and denied entry. The woman and the heart are said to mean that women are waiting at that building and eager for affection. The coin purse tells visitors their affection can be procured, but the library is nearby if you’re out of money. A statue of Priapus (the Greek god of fertility) with an oversized phallus was excavated from the house and is now on display in the Ephesus Museum.

It is thought to have been built in the 1st century A.D., approximately the same time as the baths and the latrines. The front part was modified during Byzantine and used as a covered walkway. The brothel had two entrances, one onto each of the intersecting streets. On the first floor, which is the only floor surviving today, there is a large salon hall for mingling and the second-floor rooms for the prostitutes to take their visitors. On the west side of the house was a reception room with a partially preserved mosaic decoration depicting the four seasons. Adjacent to the reception area is a small bathing room with a mosaic-decorated oval pool; health and cleanliness were essential, and visitors would have been required to wash their hands and feet before entering the main salon.

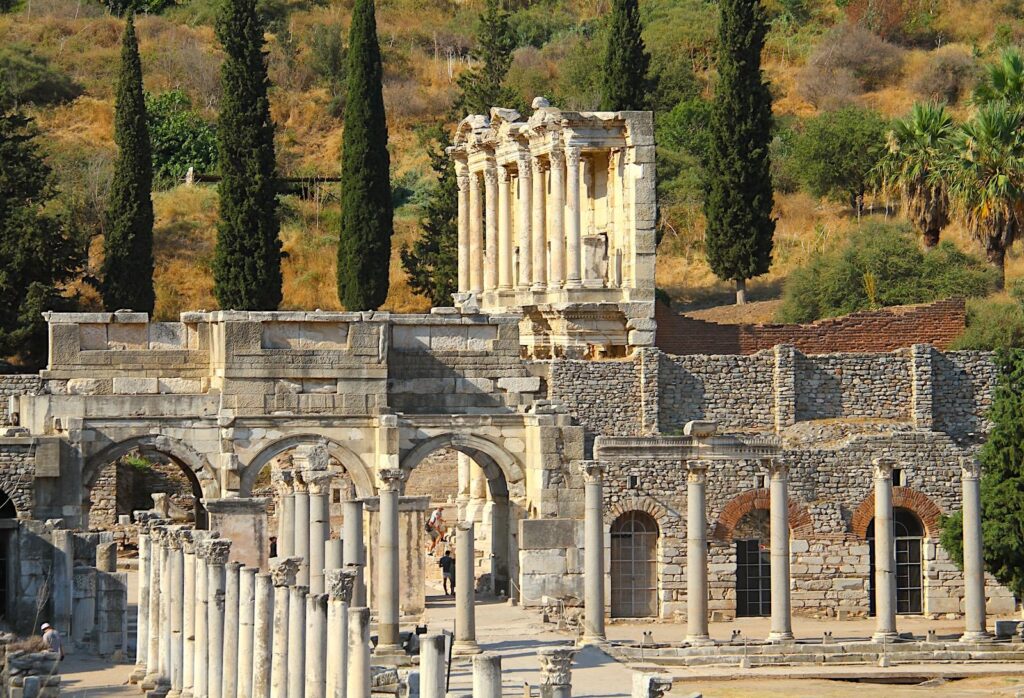

(xv) The Library of Celsus

Often represented as the postcard of Ephesus, the early 2nd century A.D. Library of Celsus’s two-storey façade was reconstructed by the German archaeologist Volker Michael Strocka between 1970 and 1978 using fragments found during excavations. The structure was supported by four pairs of columns, between which there were three entrances to the library. On the second floor of the façade are three windows, providing light to the reading room, and the statues on the façade signify the “Four Virtues”: Sophia (wisdom), Arete (bravery), Episteme (knowledge) and Ennoia (thought).

In the library’s interior is one large room of 10.9 x 16.7 meters surrounded by an additional wall to shield from moisture and above a vaulted substructure. There are two visible rows (initially three rows) of niches on the building’s inner side and rear walls, where galleries and shelves would have been mounted to hold and access the manuscripts. In the large arched central niche, the statue of the goddess Athena would have been displayed. Named after the Roman governor of Asia Minor from Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (circa 45-120 A.D.), a.k.a. Celsus, he was buried in a tomb under the library. The library construction started in 110 A.D. and also became a mausoleum by order and commission of Celsus’s son, Tiberius Julius Aquila Polemaeanus, on completion in 135 A.D.

Before 400 A.D., the interior was wrecked by fire, and the building stopped functioning as a library. The decorative façade was left intact, and the area at the front was converted into a pool reflecting the striking façade. In and around the pool, archaeologists uncovered large reliefs portraying the victory of Marcus Aurelius over the Parthians, which are now exhibited in Vienna. Some library fragments excavated by Austrian archaeologists between 1895-1906 were taken to museums in Istanbul and Vienna. During reconstruction, these fragments were replaced by copies, including the statues of the Four Virtues, as the originals are now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wein (Art Historical Museum Vienna) Ephesos Museum, an annexe to the Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

(xvi) Commercial Agora (Tetragonos Agora)

The Commercial Agora, close to the junction of Marble Road and Harbour Street (Arcadiane), also known as the Tetragonos Agora (meaning square market), dates to the Hellenistic period, around the 3rd century B.C. However, most of the structures that can be seen today were built during the Roman period, from the 1st century B.C. onward. Excavations revealed settlement on this site from the 8th century B.C., with the 3rd century B.C. agora being 3 metres below the current ground level. The Commercial Agora was primarily used as a marketplace where merchants sold their goods and was the economic heart of Ephesus. The agora also hosted various social and political activities and was a place where people gathered, discussed civic issues, and participated in public events. The agora remained in use until the 7th century A.D., maintaining its general plan. However, it lost its function as a marketplace and was used primarily for workshops.

Almost a square, the agora measures approximately 110 x 110 metres, enclosed by stoas (covered walkways) on all four sides. The collonaded walkways provided shelter for shoppers and merchants and consisted of rows of columns supporting a roof. The columns of the stoae were primarily made of marble and were designed in various orders (Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian), reflecting the architectural styles of the period. Behind the stoas were approximately 100 shops, workshops and meeting places. Each shop typically had a small front opening onto the stoa. The open central area of the agora was used for larger market activities as the open space that allowed for the setup of temporary stalls and booths. The agora had monumental gates on three sides (north onto Harbour Street, southeast close to the Library of Celsus, and on its west side), providing grand entrances to the marketplace. These gates were decorated with intricate carvings and inscriptions, celebrating various emperors and benefactors. Surrounding the agora were several important public buildings and monuments, including temples, fountains, and administrative buildings, adding to the significance of the agora as a civic centre.

(xvii) The Gate of Mazeus and Mithridates

The Gate of Mazeus and Mithridates is a monumental gate near the Library of Celsus, at the southeast entrance to the Commercial Agora, constructed in 3-4 A.D. by two freedmen, Mazeus and Mithridates. Three Latin and Greek inscriptions over the gate are dedicated to their benefactors: Emperor Augustus (Octavian Augustus), his wife Livia, his son-in-law Marcus Agrippa, and Julia the elder, the daughter of Augustus and the wife of Agrippa. These dedications were a mark of gratitude for their release from slavery. The gate thus not only served as a functional entryway but also as a political and social statement, emphasizing the power and benevolence of the emperor and his family. The inscriptions were made of gold-plated bronze letters, but only their mounting holes remain today. While the primary function of the gate was to serve as a grand entrance to the Commercial Agora and facilitate the flow of people and goods into and out of the marketplace, the gate also had a ceremonial purpose, acting as a monumental backdrop for public events and gatherings.

The gate, largely constructed using marble, comprises three arched passageways, with the central arch larger than the two flanking arches. This tripartite design was common in Roman triumphal arches, symbolizing grandeur and triumph. Each arch is flanked by pairs of Corinthian columns, which support an entablature. The entablature above the columns includes inscriptions dedicated to Augustus and his family. Above the entablature, the gate features an attic story, which formerly displayed statues and additional decorative elements. The gate was adorned with reliefs and sculptures that depicted various scenes and motifs, including mythological figures and possibly scenes from the life of Augustus. Analysis of the style of the decorations of the left and right parts of the gate indicated that different teams of sculptors had been responsible for their production. The gate is currently in the condition following the restoration project between 1980 and 1989, where the southern façade was fully restored, almost exclusively using the original ancient building materials.

(xviii) The Great Theatre of Ephesus

The theatre’s construction began in Hellenistic times and was enlarged later during the reign of Roman Emperor Claudius (10 B.C. – 54 A.D., reign 41-54 A.D.). The two-storey stage (skene) was built during the reign of Emperor Nero (37-68 A.D., reign 54-68 A.D.), and the third storey was added in the mid-2nd century. Its construction was completed only in the times of Emperor Trajan (53-117 A.D., reign 98-117 A.D.). In the early 2nd century A.D., an aqueduct was built to bring water to Ephesus for the Trajan nymphaeum, with its course requiring a channel through the upper section of seats.

Between 359 and 366 A.D., the theatre was damaged by the earthquakes that wrecked the upper cavea. Some repairs to the northern walls were done during the reign of Arcadius (377-408 A.D., reign 395-408 A.D.), but the upper cavea was abandoned. An epigram mentions the proconsul Messalinus, who was responsible for completing these repairs. In the 8th century A.D., the theatre became a part of the defensive fortifications of Ephesus.

The theatre rises 30 meters high with a diameter of 145 meters; it would have seated approximately 25,000 spectators and is believed to be the largest in the ancient world. It was constructed so the audience would face the 25 x 40-metre stage and have the harbour in the background. Primarily used for drama, later in Roman times, gladiatorial combats were also held on its stage, and archaeological evidence of a gladiator graveyard was found in May 2007. An altar in the middle of the stage podium would have offered sacrifices on feast days. During the Roman era, plays started in the early morning and often continued until midnight. The theatre was one of the first structures excavated by archaeologists before the First World War, and in the 1970s and 1990s, the cavea was completely excavated and restored.

The theatre is often included in lists of local sacred destinations because of its biblical significance and is repeatedly mentioned in the framework of St. Paul’s visit to Ephesus. A misconception is that he sermonised in the theatre, but there is no historical verification of St. Paul’s presence at the theatre, and at that time, it was under reconstruction. According to the Bible accounts in the Acts of the Apostles (19:23-41), St. Paul was encouraged by his friends not to enter the theatre, and the riot provoked by Demetrius forced Paul to leave the city.

Acts 19:23-34: The Riot in Ephesus

New International Bible – Acts 19:23-34

(23) About that time, there arose a great disturbance about the Way. (24) A silversmith named Demetrius, who made silver shrines of Artemis, brought in a lot of business for the craftsmen there. (25) He called them together, along with the workers in related trades, and said: “You know, my friends, that we receive a good income from this business. (26) And you see and hear how this fellow Paul has convinced and led astray large numbers of people here in Ephesus and in practically the whole province of Asia. He says that gods made by human hands are no gods at all. (27) There is danger not only that our trade will lose its good name but also that the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be discredited, and the goddess herself, who is worshipped throughout the province of Asia and the world, will be robbed of her divine majesty.”

(28) When they heard this, they were furious and began shouting: “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” (29) Soon, the whole city was in an uproar. The people seized Gaius and Aristarchus, Paul’s travelling companions from Macedonia, and all of them rushed into the theatre together. (30) Paul wanted to appear before the crowd, but the disciples would not let him. (31) Even some of the officials of the province, friends of Paul, sent him a message begging him not to venture into the theatre.

(32) The assembly was in confusion: Some were shouting one thing, some another. Most of the people did not even know why they were there. (33) The Jews in the crowd pushed Alexander to the front, and they shouted instructions to him. He motioned for silence in order to make a defence before the people. (34) But when they realized he was a Jew, they all shouted in unison for about two hours: “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

Source: Biblegateway.com

(xix) Vedius Gymnasium and Baths

The Vedius Gymnasium, built 147-149 A.D., was commissioned by Publius Vedius Antoninus and his wife, Flavia Papiane, who dedicated the gymnasium to goddess Aphrodite, and Emperor Antoninus Pius (86-161 A.D., reign 138-161 A.D.). The 135 x 85 meters building served both as a gymnasium and baths. East of the gymnasium is the palestra, with a monumental gate on the southern side surrounded by covered arcades of the courtyard. In the Palestra, wrestling and other sports were practised. The porticoes were used as locker rooms, warehouses, and changing rooms. The gate was decked with statues, and its western side housed a toilet. The principal room of the gymnasium stretched along the entire width of the building on the eastern side and was used for physical exercises. The central room of the building served as the frigidarium (cold room) and was decorated with the statue of the god of the River Kaistros, dispensing water into the pool from the amphora. This statute is on display in the Izmir Archaeological Museum. The Vedius Gymnasium at Ephesus is just outside the main archaeological site, in a fenced-off area on the road to the lower entrance.

(xx) The Church of Mary in Ephesus

The first Christian church named after the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ, was the Church of Mary in Ephesus, which Emperor Constantin I (272 -337 A.D. Emporer 306 – 337 A.D.) commissioned in the 3rd century A.D. It is the most significant building from Christian times in Ephesus and is located within the Ephesus Ancient City museum site close to the north entrance. Before it was converted to a church, the building was used to stock wheat. The third ecumenical council in 431 A.D. was held here to end the controversies concerning the divinity of Christ and the sanctity of the Holy Virgin. The council ruled that God was one being, though two natures, the Father and the Son, and that the Virgin Mary was indeed the mother of Christ (Theotokos meaning “[she] whose offspring is God”). In the early times of Christianity, churches were dedicated to those who lived and died in the same province. An inscription dating back to the third ecumenical council was found saying, “We are writing from the house where our mother Mary lived and died.

The church can be described as a basilica with a nave and two aisles. The aisles were divided into shorter parts, which could serve as shops. Today, the best-preserved section of the structure is a cylindrical baptistery located in the northern part of the atrium. In the central part of the baptistery was a pool where the baptised people could be fully immersed in water. Ephesus was a city that received one of the Letters of Paul from the New Testament. The Gospel of John may have been written in the city, and it was the site of several 5th-century Christian Councils, the Council of Ephesus.

In the 7th century, the church fell into ruin. The Byzantines raised a new church on the same site, and over time, the church was rebuilt several times, so the structure we can see today does not reflect the church’s appearance from the time of the Council of Ephesus or the later 8th-century building. Instead, it represents the late Byzantine period when the domed church fell into ruin and was eventually abandoned. It was replaced by a new basilica, which had much smaller dimensions and was built into the space of the old church. Finally, the whole structure collapsed and was turned into a cemetery. It is unknown when the collapse happened, but there are mentions of the old church with the icon of the Virgin Mary from the 12th century, so it probably survived at least until this period.

(xxi) The Harbour & Harbour Baths

Before the 3rd century B.C., since its foundation around the 10th century B.C. by Ionian Greeks, the city and harbour of Ephesus were centred around the Temple of Artemis in current Selçuk. During the Ionian, Lydian and Persian periods, the harbour played a pivotal role in the city’s development and prosperity, making it one of the most important ancient ports in the Mediterranean. The location near the mouth of the Cayster River (Küçük Menderes) made it an ideal spot for a harbour and the city. After the conquest of Alexander the Great in the late 4th century B.C., Ephesus came under Macedonian control, and its harbour benefited from increased trade and Hellenistic cultural influences. Alexander’s general, Lysimachus, further developed Ephesus in the early 3rd century B.C., moving the city to this new location and improving its harbour facilities to support larger ships and increase commerce. When in 133 B.C. Attalus III of Pergamon bequeathed his kingdom to Rome; the harbour saw significant enhancements and became a major Roman commercial hub. Emperor Augustus transformed Ephesus into the capital of the Roman province of Asia around 27 B.C., further improving the harbour to facilitate increased trade and administrative functions. The 1st and 2nd centuries A.D. marked the golden age of Ephesus’ prosperity, and the harbour was bustling with activity, serving as a crucial point for importing goods from the eastern provinces and exporting products to Rome and other parts of the empire. Commodities like silk, spices, and grain flowed through the port. Over time, the harbour began to silt up due to sediment deposits from the Cayster River. Despite several attempts by the Romans to dredge and maintain the harbour, the problem persisted. The harbour remained active during the early Byzantine period, but its usefulness declined due to ongoing siltation. By the Middle Ages, the harbour was largely abandoned. The coastline had shifted, and the once-thriving port was no longer accessible to large ships. Ephesus itself gradually declined, and its population moved inland.

The central square of the harbour district of Ephesus was the Hall of Verulanus, an expansive square measuring 200 x 240 metres. It was the largest of the sports facilities situated along Harbour Street. It was named after the founder, Verulanus, who was the chief priest of Asia during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. The arcaded courtyard served as training grounds for the athletes and was surrounded by a three-aisled colonnade, with its broad middle aisle serving as a running track. Part of the ruined Hall of Verulanus has been unearthed by the archaeologists adjacent to the Church of Mary. The remains of the Harbour Baths stand to the west of the Hall of Verulanus, though only a minor part of the complex has so far been uncovered.

The 1st century Harbour Baths are the oldest in Ephesus and were probably erected during the reign of Emperor Domitian (51-96 A.D., reign 81-96 A.D.). They were renovated during the reign of Constantius II (317-361 A.D., reign 337-361) and, as such, are also known as the Constantine Baths. The complex consisted of two palaestrae, with a total length of 360 meters, a double-level gymnasium building of 40 x 20 meters with a palaestra in the centre, surrounded by rooms of different functions. The hall in the northern part of the smaller palaestra was dedicated to the imperial cult. In the excavations of the gymnasium, a Roman copy of a Greek bronze athletes’ statue was found together with a life-size marble statue of a baby boy with an Egyptian goose; these artefacts are now on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna.

The Ephesus Experience Museum

Ephesus Experience Museum Website – Tel: 0850 346 33 36 – opening times: daily 08:00-22:00

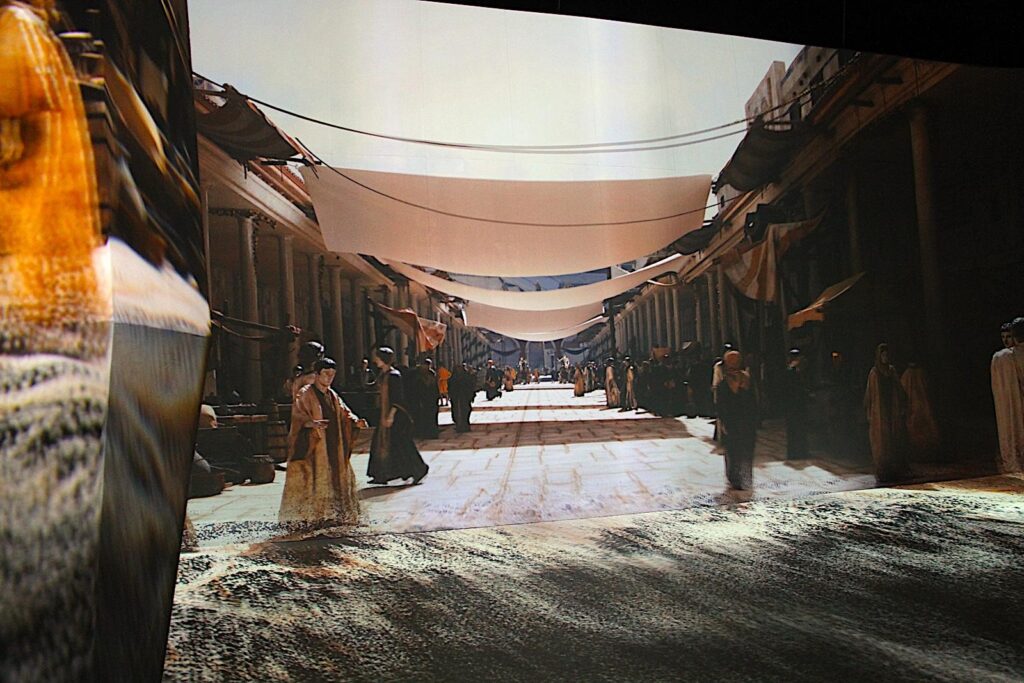

The Ephesus Experience Museum, located within the Ephesus Archaeological Site near the Great Theatre of Ephesus, is a modern, interactive museum designed to give visitors an immersive experience of one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites. Visitors proceed through three halls in groups, and the experience sets out to retell the city’s rich history and daily life during its golden age. As of July 2024, the entrance cost is included as part of the €40 overall Ephesus entry ticket, but an additional (TL425 – approx. €12) to visitors on the MüzeKart or MuseumPass. The audio narrative is provided on a system of synchronised headsets distributed on the entry in a diverse range of languages. Near the entrance is a modern air-conditioned coffee shop, and the Ephesus Museum shop is at the presentation’s exit.

OTHER ANCIENT SITES AROUND EPHESUS

The sites below are outside the Ephesus Archaeological Site; their respective locations and entry details are noted.

The Temple of Artemis (Selçuk)

Location: Artemis Tapınağı, Atatürk, Park İçi Yolu No:12, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir– Access from Dr Sabri Yayla Blvd. Open daily 08:30-17:30 – Free entry.

In its day, Ephesus was famed for the nearby Temple of Artemis, built circa 550 B.C. Today, it is just west of the centre of Selçuk and was designated one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was a gigantic building; however, all that remains are a single column and some temple debris. The temple was the largest building in the Hellenistic world, exceeding the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens and the first monumental structure built entirely of marble.

Before the arrival of the Greeks, a sanctuary to the mother goddess Cybele stood at the site. later, Cybele was recognised by the Greeks, and many of her features were assimilated with the goddess Artemis. Late 19th-century digs by the British uncovered evidence of three earlier buildings: a simple altar and two small naiskos (temples in classical order with columns and pediments). It is understood that the original temple was destroyed during a flood in the 7th century B.C.

The 6th century B.C. was the peak of the Ionian colonies in Asia Minor, and prosperous cities such as Ephesus required grand temples to express their importance. Circa 570 B.C., in competition with the newly erected large temple on the nearby island of Samos, Ephesus resolved to construct an even more magnificent sacred building. Commissioned by King Croesus of Lydia (reign 585-546 B.C.) employing renowned Cretan architects, Chersiphron and his son Metagenes and architect Theodoros, experienced in building on marshy grounds such as at Ephesus, developed a distinctive colossal structure inspired by Egypt and Urartu (Armenian Highlands). Its base exceeded 55 x 115 metres, with the marble temple surrounded by a double colonnade of 127 columns, 19 meters high, including 36 at the front. The Temple of Artemis (a.k.a. Artemision or Temple of Diana) was built entirely of marble. A cedarwood statue of the goddess Artemis stood at its centre, and famous sculptors, including Phidias and Polykleitos, were hired to decorate the temple.

For two hundred years, Artemision was the source of the glory for Ephesus; however, in 356 B.C., the temple was said to have been burned by Herostratus, who deliberately acted in arson and set fire to the wooden frame of the roof. Alexander the Great visited Ephesus in 334 B.C., offered sacrifices in the ruins of Artemision, and expressed his wish to rebuild the temple. By 323 B.C., the third temple was built as a copy of the previous form on a 13-step podium with slightly shorter 17.65-metre columns. This temple was destroyed in 262 A.D. during the invasion of the Goths in 262 AD and was never reconstructed.

Having searched for the Artemision ruins for over 60 years, they were discovered by an expedition funded by the British Museum in 1869. The initial works of archaeology continued until 1874 and again from 1904 to 1906. These works uncovered the foundations, and the chronology of the temple’s construction could be understood. These temple remains were removed and are now displayed in the “World of Alexander” (room 22) in the British Museum (London). Between 1896 and 1906, Austrian archaeologists also worked in Artemision, and they discovered and removed an altar and a statue of a wounded Amazon, which are now exhibited in Kunsthistorisches Museum Wein (Vienna) – Ephesos Museum, an annexe to the Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

See also: LikeCesme.com – Ephesos Museum Exhibition in Vienna

The Basilica of St. John (Selçuk)

Location: İsa Bey, 2013. Sk. No:1, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir – Open daily 08:00-18:00 (Summer: 1 April-31 October), Winter 08:30-16:30 – Ticket price approx. €TBC.

The basilica is just northwest of the current day Selçuk, 1km from the Temple of Artemis. It was built in the 6th century under Emperor Justinian I (482 – 565 A.D. Emporer 527 – 565 A.D.) over the supposed site of the St. John Apostle’s tomb. Not to be mixed with John the Baptist, the John who was buried here is John the Apostle. It is believed that at his crucifixion, Jesus asked his beloved disciple, John, to look after his mother. He and the Virgin Mary travelled to Ephesus between 38 and 47 A.D., where he resided. John was exiled to Patmos for eight years by Emperor Domitian. Later, he returned to Ephesus and continued writing the Gospel. It is said that John was martyred at the age of 98 under the rule of Emperor Trajan.

The hill that John was thought to have lived after coming from the island of Patmos was named Hagia Theologos, meaning “Holy Theologian”. It is also the name given to the city during the Byzantine period. When active, the Basilica of St. John was the second-largest church in Anatolia. The impressive ruins of the basilica are still visible. The basilica had a cross plan with six domes. Under the central dome was the sacred grave of St. John. Pilgrims have believed that a fine dust from his grave has magical and curative powers. In the apse of the central nave, beyond the transept, is the synthronon, semicircular rows of seats for the clergy. To the north, the transept was attached to the treasury, which was later converted into a chapel. The baptistery is from an earlier period and is now located north of the nave. Mosaics used by Byzantines are smaller than Roman mosaics, and examples can be noticed in the treasury.

İsa Bey Mosque

Location: İsa Bey, 2040. Sk. no:2, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir Adjacent to the Basilica of St. John in Selçuk

The İsa Bey Mosque was commissioned by İsa Bey, a member of the Aydinid dynasty, and constructed between 1374 and 1375. The mosque was designed by the architect Ali bin Mushimish al-Damishki. The mosque represents a critical period in Anatolian history when the Seljuks were transitioning to the early Ottoman Empire, showcasing a blend of Seljuk and local architectural influences. Over the centuries, the mosque fell into disrepair, especially after an earthquake in the 17th century. Restoration efforts have been undertaken to preserve this historical structure, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries. The İsa Bey Mosque is notable for its rectangular plan and the use of space, measuring approximately 51 x 57 metres. The mosque features a large courtyard surrounded by a collonaded peristyle, typical of Seljuk mosque architecture. The prayer hall is divided into two sections by a central arcade, with the main hall covered by two domes that rest on octagonal drums and are supported by pointed arches. The mosque was built using a combination of cut stone and marble, with columns and other architectural elements from earlier Roman and Byzantine structures reused. Originally, the mosque had two minarets; however, only the minaret on the southwest corner of the mosque survived.

House of St. Mary in Ephesus

Location: Atatürk Mahallesi, Meryemana Mevkii, Küme Evler, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir – Opening Hours: 08:30-17:00 – House of St. Mary in Ephesus English Website

At the top of the hill, 5.5km south of the Upper Gate (south entrance) of the Ephesus Ancient City Museum, is the House of St. Mary in Ephesus. While there is no direct archaeological evidence or mention in the Bible, the House of the Virgin Mary is where, according to many people’s beliefs, Mary, the mother of Jesus, spent the last years of her life. It is supposed that Mary arrived at Ephesus with St. John and lived there until her death and Assumption/Dormition*. A synodal letter of the Council of Ephesus that took place in 431 A.D. mentions “the city of the Ephesians, where John the Theologian and the Virgin Mother of God St. Mary [lived and are buried]”.

While the Roman Catholic Church has never pronounced the house’s authenticity for the lack of scientifically acceptable evidence, many gestures made by Popes authenticated its history in the eyes of the faithful. An investigation commissioned by the Archdiocese of Smyrna concluded in December 1892 that the assumption that the Blessed Virgin Mary might have died in the house was scientifically and theologically justifiable. An Austrian excavation team conducted two exploratory excavations on behalf of the Turkish Heritage Authority in 2003. The analysis of the ceramic finds from undisturbed excavation layers concluded that the ancient villa was the atrium of a residential house from the 1st century A.D.

Ephesus Archaeological Museum (Selçuk)

Location: Atatürk, Uğur Mumcu Sevgi Yolu No: 26, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir – Open daily 08:00-19:00 (Summer: 1 April-31 October), Winter 08:30-17:30 – Ticket price approx. €TBC.

Many of the findings from the area, including those from Ephesus and the Temple of Artemis, were removed from the country. Artefacts excavated between 1867 and 1905 were taken to the British Museum, and those from 1905-1923 were taken to Austria, where they are now exhibited in the Ephesos-Museum der Antikensammlung des Kunsthistorischen Museums Wien (Ephesus Museum in Vienna). When Turkish law forbade taking the archaeological findings out of the country, a warehouse and later a museum was constructed in Selçuk in 1929 to protect the excavated artefacts from Ephesus and other nearby sites.

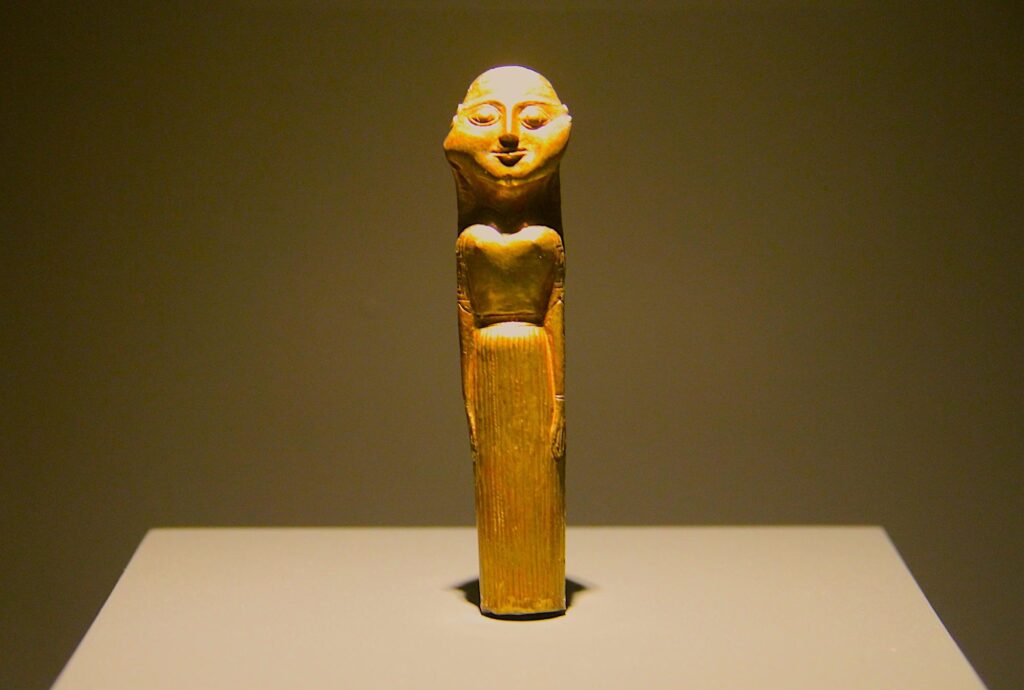

Founded as a depository in 1929, remodelled into a museum in 1962, and expanded and modernised in 2014, the relatively small museum is structured by subject and location of artefact discoveries around Ephesus, including the Hall of Fountain, the Hall of Terrace Houses, ancient coins, Ephesus through the ages, the Inner Garden, the Cybele Cult, the Hall of Artemis Temple, Ephesus Artemis, Imperial Cult Artefacts, Çukuriçi Mound, the Temple of Artemis (Artemision), the St Jean Church, and the fortress on Ayasuluk Hill. The displayed objects date back to the Mycenean, Archaic, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Turkish Republic periods.

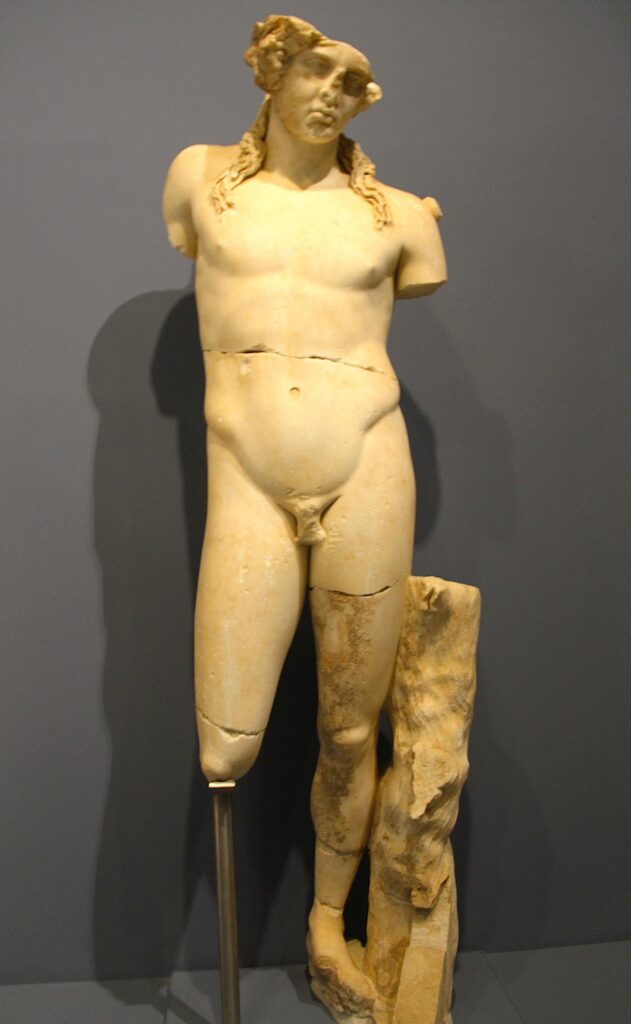

Amongst the exhibits is the statue of a young warrior exhumed from the Pollio Fountain, depicted in a half-lying position holding a shield in his arm and a sword in his hand. The white marble statue of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius dates to the 2nd century A.D. A marble sculpture of Eros’s head is broken at the neck, gazing towards the bow he holds with a childlike expression, created between 330-320 B.C.

A 2nd century A.D. statue of Artemis named by Austrian archaeologist Franz Miltner (1901-1959) as “Beautiful Artemis” has integrated features of Kybele, wearing earrings and a pearl necklace, and under her chest, four rows of globules related to fruitfulness and fertility, a thin belt adorned with bee motifs (the symbol of Ephesus) and figures of lions, rams, deer, gryphons, and bees in rectangular patterns. The statue, known as Colossal Artemis because of its size, dates back to the 1st century A.D. and has decoration on top of the head of Artemis, consisting of two rows of reliefs depicting temples, tabs on the chest of the statue are similar to breasts. However, other hypotheses suggest that they are eggs of bees or testes of bulls sacrificed to the goddess. Both the statues of Artemis were found in 1956 at the Prytaneion in Ephesus.

An intriguing exhibit in the Hall of the Imperial Cult is the Parthian Monument, whose reliefs were discovered in front of the Celsus Library, set as a fountain basin. They illustrate the scenes from the wars fought with the Parthians by emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, the latter of whom established a camp in Ephesus during his Parthian Campaign of 161-165 A.D. A monument close to the exit of the final hall portrays Proconsul Stephanus, who served as the governor of Ephesus. As part of seven late antique statues from Ephesus that date to the early 5th/mid 6th century, this group of statues are the largest uniform series of late antiquity monumental statues unearthed in any ancient Roman city.

Çukuriçi Höyük (Cukurici Mound)

Location: Atatürk, 35920 Selçuk/İzmir – Note: Access roads from the D550 have been blocked, and the site is inaccessible by car. Foot/off-road vehicle access is via the country track off Meryem Ana Yolu.

The Çukuriçi Höyük (in English, ‘Mound in the Valley’) is a prehistoric Tell (artificial topographical mound feature) settlement approximately 2km south of Selçuk and 2km southeast of the ancient city of Ephesus. Between 2007 and 2016, the settlement was thoroughly examined. The excavations at Çukuriçi Höyük revealed not only the oldest settlement of Ephesus but also one of probably the oldest settlement sites in Western Anatolia. The Neolithic Tell was first settled in the period of approx. 6700-6000 B.C. and was reoccupied in the Late Chalcolithic to the early Bronze Age circa 2800-2750 B.C.

An unusual Neolithic find at the site was a cache of long and sharp obsidian (volcanic glass) blades found inside a building. They are unique in the Aegean and show the extensive interactions of the Neolithic residents in the region. The raw material comes from the island of Milos, 300 km west of Ephesus. Examination has also revealed that local potters produced high-quality, thin-walled containers, probably used for the storage and consumption of food. Fish was part of the diet, and the remains of a tuna were found. Diet was varied, based mainly on reared pork, lamb/mutton, goat, and beef, and supplemented by wild hare, fox, red deer, auroch (extinct wild cattle) and shellfish. The nautical skills of this civilisation are shown by the remnants of deep-sea fish suggesting sea voyages beyond the Aegean Sea.

OTHER INFORMATION ON EPHESUS

UNESCO World Heritage Site

Ephesus was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Property with “Outstanding Universal Value” in 2015 based on three primary criteria, including (iii) Ephesus is an exceptional testimony to the cultural traditions of the Hellenistic, Roman Imperial and early Christian periods as reflected in the monuments in the centre of the Ancient City and Ayasuluk. (iv) Ephesus as a whole is an outstanding example of a settlement landscape determined by environmental factors over time. The ancient city stands out as a Roman harbour city, with a sea channel and harbour basin along the Kaystros River. And (vi) Historical accounts and archaeological remains of significant traditional and religious Anatolian cultures, beginning with the cult of Cybele/Meter until the modern revival of Christianity, are visible and traceable in Ephesus, which played a decisive role in the spread of Christian faith throughout the Roman Empire.

The Church of Ephesus in the Book of Revelation

The first church mentioned in the Book of Revelation is the Church of Ephesus. To this church, Jesus commended them for their endurance, longsuffering, and dislike of false doctrine and evil behaviour. He chided them. However, Revelation 2.4 says, “…you have abandoned the love you had at first”. They no longer had the burning, consuming passion for their God they had when they were first saved and settled into the routine of the faith. He encourages them to find that fire again and continue where they were doing well.

Revelation 2:1-7 – Letter to the Church in Ephesus

Revelation 2:1-7

(1) “To the angel of the church in Ephesus write:

These are the words of him who holds the seven stars in his right hand and walks among the seven golden lampstands. (2) I know your deeds, your hard work and your perseverance. I know that you cannot tolerate wicked people, that you have tested those who claim to be apostles but are not and have found them false. (3) You have persevered and have endured hardships for my name and have not grown weary.

(4) Yet I hold this against you: You have forsaken the love you had at first. (5) Consider how far you have fallen! Repent and do the things you did at first. If you do not repent, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place. (6) But you have this in your favour: You hate the practices of the Nicolaitans, which I also hate.

(7) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches. To the one who is victorious, I will give the right to eat from the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Seven Churches of Revelation“

SOCIAL MEDIA ON EPHESUS

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture & Tourism – Ephesus Archaeological Site English Website – Ayasuluk Archaeological Site (Ayasuluk Castle & St. Jean Monument) English Website – Ephesus Museum English Website – The Terrace Houses English Website (includes links to their respective .pdf brochures)

Turkish Museums – İzmir Ephesus English Website – İzmir Ephesus Museum English Website – İzmir St. John Monument English Website

UNESCO World Heritage Convention List – No. 1018 – Criterion for UNESCO Listing Ephesus English Website

LikeCesme.com: Ephesos Museum Exhibition in Vienna

LikeCesme.com: Seven Churches of Revelation