Located at the foot of the Tmolus mountains, on the verge of the fertile Hermus plain, Sardis Ancient City is on a major route connecting the Aegean with inland Turkey, around a naturally secure fortress by the banks of the Hermus (Gediz) river. Sardis was privileged and had many natural advantages, and it became the capital of the Lydian empire in the 7th and 6th centuries B.C. The ancient name of the city derives from the Lydian “Sfar”, later Sparda in Persian and Sfard (Σάρδεις) in Greek. The town of Sart, which borders the ancient sites to the north and west, still reflects the roots of the town’s name.

Getting there: 1km south of the centre of Sart and 185km east of Çeşme in the province of Manisa via the E881 highway and E96. 2 hour drive by car via İzmir and Turgutlu.

Map location & entry: Zafer, Belediye Cd. No:124, 45300 Salihli/Manisa. – Open daily 08:00-17:00 (31 Oct- 1 Apr) and 08:00-19:00 (1 Apr—31 Oct). Ticket price approx. €TBC.

Sardis Ancient City – Table of Contents

Brief History of Sardis

The Mermnadae dynasty of kings from Gyges (c. 680-644 B.C.) to Croesus (c. 585-546 B.C.) conquered western Anatolia, invented the world’s first coins, and established treaties with the major civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece. Its kings were legendary for their wealth and generosity, building temples and dedicating precious objects and gold at Greek sanctuaries such as Ephesus, Didyma and Delphi. The lower city was defended by a massive fortification 20 metres thick. Sardis’ royal necropolis burial mounds at Bin Tepe (10-15km north of Sart, between Kendirlik and Tekelioğlu) are among the world’s largest.

Conquered by Cyrus the Great (c. 600-530 B.C. reign 550-530 B.C.), between 547 and 334 B.C., Sardis was the capital of a central province of Asia Minor under the Achaemenid Persians and the staging post for the invasions of Greece under Darius the Great (c. 550-486 B.C. reign 522-486 B.C.) and Xerxes the Great (c. 518-465 B.C. reign 486-465 B.C.). Following the conquest of Alexander the Great in 334 B.C., Sardis joined the Hellenistic kingdoms and was the western capital of the Seleucid empire. The city passed between Hellenistic rulers and the Attalids for the next two centuries. It was besieged by Seleucus I in 281 B.C. and Antiochus III in 215-213 B.C., but neither succeeded in breaching the fortified acropolis. Jewish communities settled at Sardis in the 3rd century B.C. The Sardis Synagogue was built around this time, remaining active into Late Antiquity. The citadel of Sardis was celebrated throughout history and was described by the Greek historian Polybius (c. 200-118 B.C.) as “the strongest place in the world”. The city sometimes served as a royal residence but was governed by an assembly.

In this era, the Greek language replaced the Lydian, and principal buildings were erected in Greek architectural styles, including a prytaneion, gymnasium, theatre, hippodrome, and the enormous Temple of Artemis visible today. In 129 B.C., Sardis passed to the Romans and prospered under the peace of the early Roman era. The city featured a temple of the imperial cult, baths, a stadium, aqueducts, and other civic buildings. While no church remnants have been found dating to the era of John the Apostle (c. 6-100 A.D.), Sardis is famous as one of the Seven Churches of Asia in the Book of Revelation.

Under Emperor Diocletian (c. 242-311 A.D. emperor 284-305 A.D.), Sardis became a provincial capital of Lydia, thriving particularly in the 4th and 5th centuries A.D. The late Roman synagogue of Sardis is the largest known synagogue of the ancient world. The city’s churches included a 4th-century church outside the city walls, a chapel attached to the temple of Artemis, and a large basilica near the city’s centre. Late Roman houses and the “Byzantine Shops” at the city’s periphery attest to its growing size and population. As with many other contemporary cities of the era, Sardis declined through the 6th and early 7th century A.D., and the lower city was mainly abandoned by the 7th century. The Acropolis remained an important citadel and stronghold through the Byzantine period.

Sardis Ancient City

The Altar and Temple of Artemis

The structure was built following the peripteros plan (Greek or Roman temple surrounded by a portico with columns) in the Hellenistic period circa 3rd century B.C., with later additions and changes to the Roman period. It is the world’s fourth largest Ionic order temple. It is constructed using marble, with rounded and embroidered column bases on square pedestals and fluted column shafts with intricately carved Ionic column heads. The temple interior featured a large central nave and smaller chambers dedicated to religious purposes to Artemis, the goddess of hunting, fertility, and soil. The city of Sardis traded gold and silver, and the temple was a hub for these industries; the large treasury attracted many merchants and traders.

The construction of the cella (central room containing the deity’s image or statue), including the columns between the anta walls of the front and back porches, was most likely conceived and developed in the 3rd century or 2nd century B.C. Although the temple was used during this period, none of the outer columns had been built. The construction of the exterior colonnade belongs to the Roman Imperial era. Sometime during the first half of the 2nd century A.D., the cella was divided into two equal chambers and the temple was incorporated into the Imperial Cult, as attested by the discovery of numerous colossal portraits of the Roman emperors of the Antonine family and their consorts inside or immediately around the building. The gigantic structure was still unfinished by the end of the 4th century A.D. when it was abandoned with the coming of Christianity, and a small church was erected at the southeast corner. Dozens of crosses crudely carved on its marble walls testify to the attempt to regain the magnificent pagan structure for a new use.

Gymnasium Complex

The gymnasium at Sardis dates back to the Roman era, when it was used for physical training, education, and socialising. It consisted of several buildings and outdoor spaces, and the central rectangular building had two floors. The lower floor had a central courtyard surrounded by rooms, while the upper floor was the gymnasium. The gymnasium’s ample open space was used for exercise, running, and other physical activities. The complex also had a swimming pool and a centre for education. Several rooms were used for classes, lectures, and discussions, making the gymnasium a hub of intellectual and cultural activities and the city’s social and cultural life.

The Byzantine Shops

The row of small shops behind the north portico of the Roman avenue on the south side of the bath and gymnasium complex leading to the synagogue formed part of a buoyant commercial district in the 5th and 6th centuries. These small structures were probably developed by civic authorities and leased to the shopkeepers to subsidise the costs of civic maintenance. Each of the shops could be partitioned or joined to meet the changing needs of their tenants, and over the 200 years they were occupied, they were constantly adapted. Before they were abandoned after a fire swept through the quarter in the early 7th century, the 34 units appeared to consist of approximately 12 working shops. They were accessed via doorways that had marble or tile floors. Stairways or wooden ladders led to an upper floor, offering storerooms and residences overlooking the lively portico and noisy avenue. Artefacts and furnishings discovered at the site indicate the range of functions of the stores: tavernas or restaurants, dye or paint vendors, and recycling of glassware or metalware. Names and religious symbols decorating artefacts or walls reveal the cultural diversity of the residents.

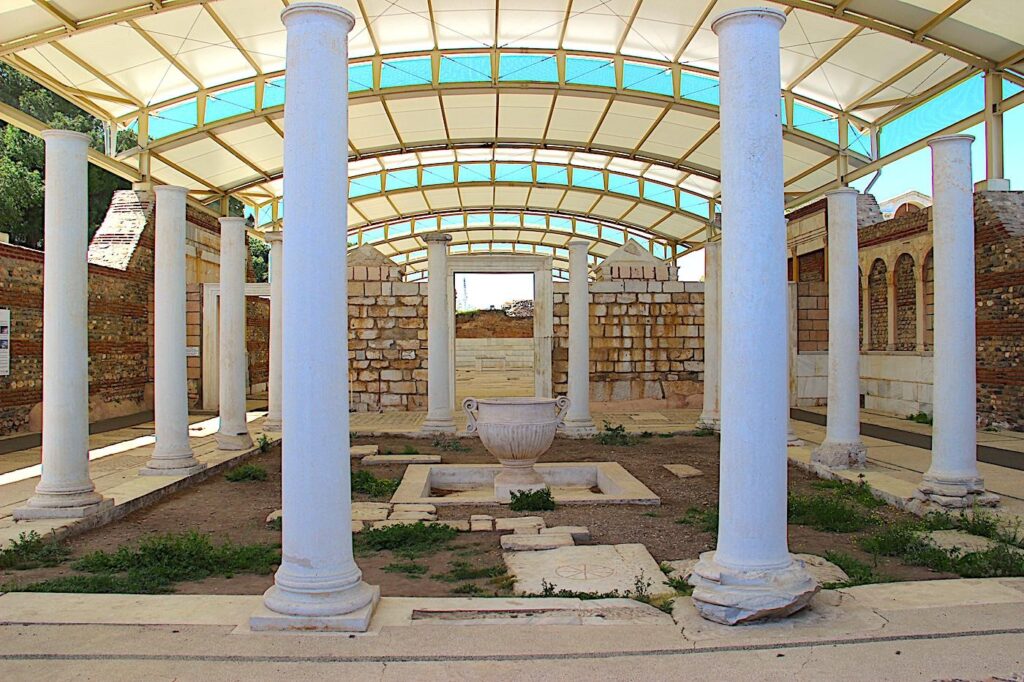

Sardis Synagogue

The substantial 3rd-century A.D. synagogue built by Jewish merchants featured a large central hall with rows of columns and ornate decorations, including elaborate mosaics and frescoes. Intricate carvings and inscriptions in Hebrew and Aramaic adorn the walls. At the time of construction, the Jewish community was experiencing significant upheaval and was transitioning from temples to synagogues.

Byzantine Churches at Sardis

Sardis gained reputation and fame as one of the Seven Churches of the Apocalypse by John the Apostle in the Book of Revelation. The Turkish government permitted international excavations to commence in 1910, during which the first of several Byzantine-style churches were discovered.

A small, 4th-century mortuary chapel known as Church M is the earliest extant Christian church at Sardis. It was built on the abandoned grounds of the Hellenistic Greek Temple of Artemis on the Acropolis and discovered in the early 1900s by a professor at Princeton on the First Sardis Expedition.

The construction of Church M within the site of the Temple of Artemis reveals the extensive transformation sweeping across the Roman empire throughout the 4th century. Official recognition of Christianity by Constantine the Great (272-337 A.D. reign 306-337 A.D.) soon heralded his establishment of the new eastern capital at Constantinople. Though the temple was probably inactive by this time, its enormous walls and magnificent columns continued to overshadow the area. Engraved crosses and religious graffiti still visible near the temple’s east entrance reveal the exertions of local inhabitants to deconsecrate the structure and nullify any remaining spiritual power of the classical cult. The end of Roman temples under Theodosius the Great (347-395 A.D. reign 379-395 A.D.) in the late 4th century may have inspired some Sardis residents to erect houses in the area and to disassemble the classical structure for building materials. Church M may have been purposed both for worshipful use by local habitants and to honour this significant change in Lydian religious traditions.

On the hillside of the road that leads to the Temple of Artemis is a partially excavated simple aisled basilica known as Church EA. The church’s proximity to the southwest walls of Sardis indicates an effort at urban expansion by creating a Christian quarter outside the defences. Identification of coins unearthed during excavation suggests it may have been built in the middle of the 4th century A.D., nearly a century before the first Christian building of its kind was erected in Constantinople. Ornamental and architectural fragments include support columns, ornately carved doorframes, and plaster decor styled with lozenge and scale-patterned borders and crosses.

In the north aisle, a vast and richly coloured mosaic floor was uncovered with geometric shapes composed of small irregularly cut tiles, and evidence of painted walls of rich blues and black exist in over 400 fragments of brick and plaster. Until the 7th century A.D., the church added an east building and west wing, a large square atrium, a north courtyard, and numerous architectural carvings. Subsequent additions and repairs throughout the medieval period indicate that the building remained active until as late as the 13th century when a small, multi-dome church (also known as Church E) with ornate exterior decoration was built over it.

The Church in Sardis in the Book of Revelation

According to the Book of Revelation, the Church in Sardis was seemingly an active church full of good works. Sardis was also a city of wealth, known for the carpet industry and minting coins. However, this church’s wealth and good works meant nothing because the church was spiritually dead. They epitomized a church that seemed good, but many had cold hearts toward the Lord. They most likely put their faith in their works, pridefully assuming they were saved or in good standing with the Lord. The message of Revelation 3:2 is, “Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God”. The church was not beyond hope but needed to find that passion for Christ again.

Revelation 3:1-6 – Letter to the Church in Sardis

Revelation 3:1-6

(1) “To the angel of the church in Sardis write:

These are the words of him who holds the seven spirits of God and the seven stars. I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. (2) Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God. (3) Remember, therefore, what you have received and heard; hold it fast, and repent. But if you do not wake up, I will come like a thief, and you will not know when I will come to you.

(4) Yet you have a few people in Sardis who have not soiled their clothes. They will walk with me, dressed in white, for they are worthy. (5) The victorious one will, like them, be dressed in white. I will never blot out the name of that person from the book of life but will acknowledge that name before my Father and his angels. (6) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches.

Source: Biblegateway.com

Tumulus Tombs

The Lydian tumulus cemetery at Bin Tepe, 10-15km north of Sart, between Kendirlik and Tekelioğlu, on the south edge of the Marmara Lake, is of archaeological significance, providing an insight into the Lydian beliefs about death. It covers an area of 74 square kilometres, consists of several important burial mounds (tumuli) and is the largest tumulus cemetery in Türkiye. The biggest is the tumulus of Alyattes, the fourth king of the Mermnad dynasty, ruling for 50 years between 635 and 585 B.C. It is 355 metres in diameter and 63 metres high; its marble chamber was explored in the 19th century. The tombs contained artefacts, including jewellery, pottery, and weapons.

The royal cemetery of Bin Tepe remains one of the most distinctive and evocative landscapes in Turkey. Its monumental tumuli proclaim and demonstrate the royal power of Sardis, as did the pyramids of Egypt or the Eastern Qing tombs of China, and the vast necropolis that grew around these royal graves is among the largest in the world.

UNESCO World Heritage Site (Tentative List)

The Ancient City of Sardis and the Lydian Tumuli of Bin Tepe were designated a UNESCO World Heritage First and Third Degree Archaeological Site in 1978 based on three criteria, including (i) Sardis was one of the preeminent cities of the ancient world, the capital of an empire that ruled western Anatolia, the birthplace of coinage, and the home of Croesus, whose name became synonymous with unimaginable wealth. (ii) Located at the border between the Greek world and the great civilizations of central Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Near East, Sardis had strong ties to both Eastern and Western cultural traditions. And (iii) Sardis was the capital and only city of the Lydians. While Lydians were settled widely throughout western Anatolia, no other city is so directly associated with this vanished civilization.

Social Media

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture & Tourism – Sardis Archaeological Site English Website (includes a link to their .pdf brochure)

UNESCO World Heritage Convention List – No. 5829 – Criterion for Sardis and the Lydian Tumuli of Bin Tepe Tentative Listing English Website

The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis – Digital Resource Centre

See also: LikeCesme.com – The Ancient Cities