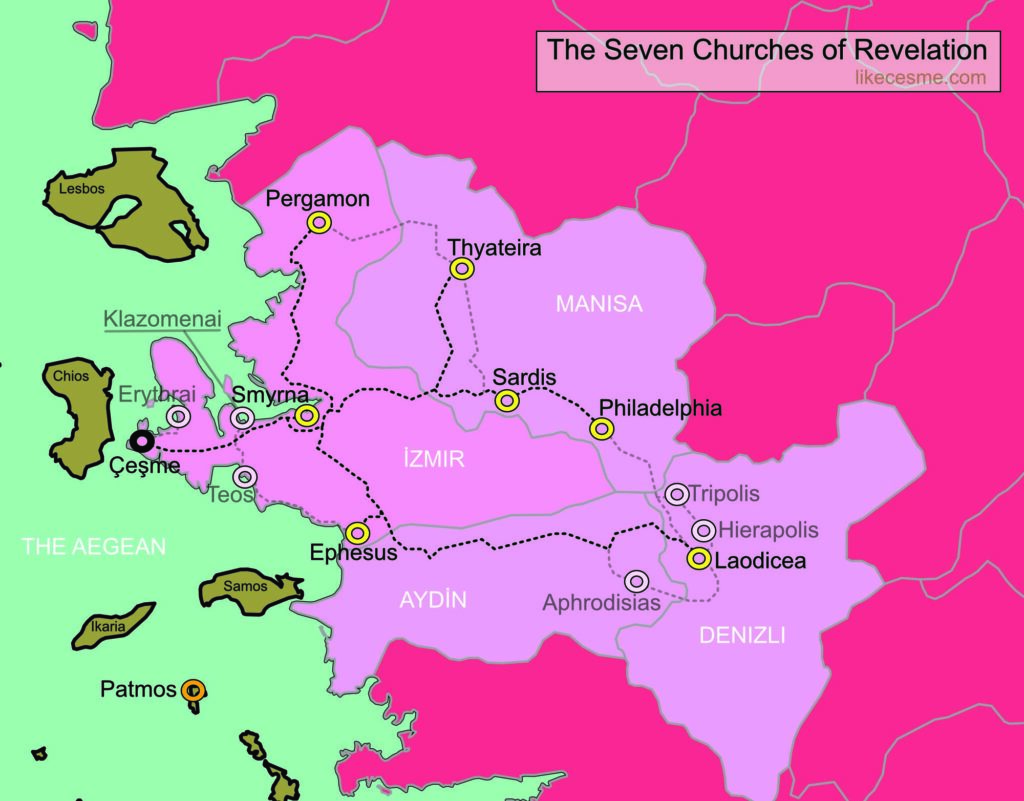

The Book of Revelation, the New Testament’s last book, addresses seven letters from John to seven churches in Asia Minor. These Seven Churches of Revelation were some of the most prominent at that time, to which John the Apostle would have been close enough to communicate effectively. The Aegean Region was also one of the central hubs of trade, commerce, and communication. The remnants of the Seven Churches of Revelation are all reasonably close to Çeşme.

John the Apostle or Evangelist John, also known as John the Theologian or John the Divine, was one of the original twelve Apostles and wrote the Gospel and the book of Revelation. He was the youngest of the twelve apostles and especially closest to Jesus. This closeness is often portrayed in icons of the Last Supper, where St. John leans on Jesus. He was present for the Transfiguration of Christ with Peter and his brother James.

The late 1st century A.D. was a time of persecution of Christians under the Romans. Emperor Domitian (51 – 96 A.D., Emperor 81 – 96 A.D.) exiled St. John to the Island of Patmos (approximately 110km south of Çeşme) around 90-95 A.D. On Patmos, he is said to have received and written the Book of Revelation. Among the 12 apostles, he is the only one not martyred but died in normal circumstances. He possibly died at the age of 98.

Below are the Seven Churches of Revelation in the order in which they appear in the Book of Revelation:

Seven Churches of Revelation – Table of Contents

The Church of Ephesus

Location: Selçuk – distance from Çeşme 155km

In its day, Ephesus was famed for the nearby Temple of Artemis, built circa 550 B.C. Today, it is just west of the centre of Selçuk and was designated one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Ephesus was a city that received one of the Letters of Paul from the New Testament. The Gospel of John may have been written in the town, and it was the site of several 5th-century Christian Councils, including the Council of Ephesus.

The city was destroyed by the Goths in 263 A.D. Although it was rebuilt afterwards, its importance as a commercial centre declined when the harbour was silted up, and in 614 B.C., an earthquake partially destroyed it.

The first Christian church named after the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ, was the Church of Mary in Ephesus, which Emperor Constantine I (272 -337 A.D., Emperor 306 – 337 A.D.) commissioned in the 3rd century A.D. It is the most significant building from Christian times in Ephesus and is located within the Ephesus Ancient City museum site, close to the north entrance. Before it was converted to a church, the building was used to store wheat.

The third ecumenical council in 431 A.D. was held here with the aim of ending the controversies concerning the divinity of Christ and the sanctity of the Holy Virgin. The council ruled that God was one being, though two natures, the Father and the Son, and that the Virgin Mary was truly the mother of Christ (Theotokos meaning “[she] whose offspring is God”). In the early times of Christianity, churches were dedicated to those who lived and died in the same province. An inscription dating back to the third ecumenical council was discovered saying, “We are writing from the house where our mother Mary lived and died.

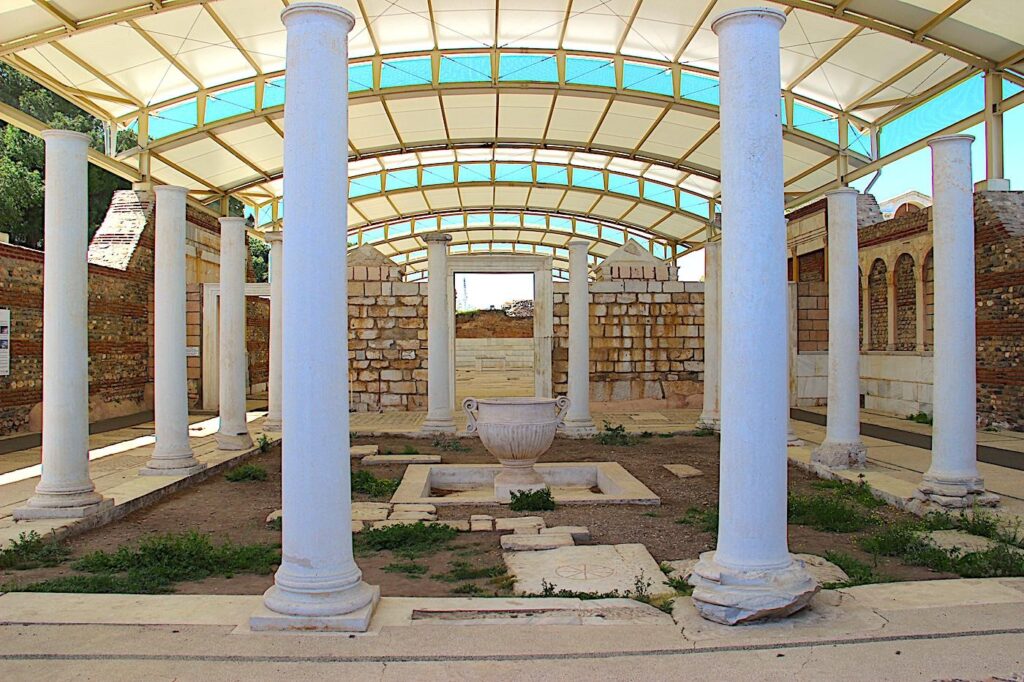

Architecturally, the Church of Mary in Ephesus can be described as a basilica with a nave and two aisles. The aisles were divided into shorter parts, which could serve as shops. Today, the best-preserved section of the structure is a cylindrical baptistery located in the northern part of the atrium. In the central part of the baptistery was a pool where the baptised people could be fully immersed in water. In the 7th century, the church fell into ruin.

The Byzantines raised a new church on the same site, and over time, the church was rebuilt several times, so the structure we can see today does not reflect the church’s appearance from the time of the Council of Ephesus or the later 8th-century building. Instead, it represents the late Byzantine period when the domed church fell into ruin and was eventually abandoned. It was replaced by a new basilica, which had much smaller dimensions and was built into the space of the old church.

Finally, the whole structure collapsed and was turned into a cemetery. It is unknown when the collapse happened, but there are mentions of the old church with the icon of the Virgin Mary from the 12th century, so it probably survived at least until this period.

At the top of the hill, 5.5km south of the Upper Gate (south entrance) of the Ephesus Ancient City Museum, is the House of St. Mary in Ephesus. While there is no direct archaeological evidence or mention in the Bible, the House of the Virgin Mary is where, according to many people’s beliefs, Mary, the mother of Jesus, spent the last years of her life. It is supposed that Mary arrived at Ephesus with St. John and lived there until her death and Assumption/Dormition*. A synodal letter of the Council of Ephesus in 431 A.D. mentions “the city of the Ephesians, where John the Theologian and the Virgin Mother of God St. Mary [lived and are buried]”.

*Countering this is the early Christian belief that St. Mary lived and died in Jerusalem, where Saint Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, testified the existence of her tomb in 451 A.D. The Church of the Dormition on the hill of Mount Zion was built at the location assumed to be Mary’s tomb in the 5th century A.D.

While the Roman Catholic Church has never pronounced the house’s authenticity for the lack of scientifically acceptable evidence, many gestures made by Popes authenticated its history in the eyes of the faithful. An investigation commissioned by the Archdiocese of Smyrna concluded in December 1892 that the assumption that the Blessed Virgin Mary might have died in the house was scientifically and theologically justifiable. An Austrian excavation team conducted two exploratory excavations on behalf of the Turkish Heritage Authority in 2003. The analysis of the ceramic finds from undisturbed excavation layers concluded that the ancient villa was the atrium of a residential house from the 1st century A.D.

The Basilica of St. John, just to the northwest of the centre of current day Selçuk, 1km from the Temple of Artemis, was built in the 6th century under Emperor Justinian I (482 – 565 A.D., Emperor 527 – 565 A.D.) over the supposed site of the St. John Apostle’s tomb. Not to be mixed with John the Baptist, the John who was buried here is John the Apostle. It is believed that at his crucifixion, Jesus asked his beloved disciple, John, to look after his mother. He and the Virgin Mary travelled to Ephesus between 38 and 47 A.D., where he resided.

Emperor Domitian exiled John to Patmos for eight years. Later, he returned to Ephesus and continued writing the Gospel. It is said that John was martyred at the age of 98 under the rule of Emperor Trajan. The hill that John was thought to have lived on after coming from the island of Patmos was named Hagia Theologos, meaning “Holy Theologian”. It is also the name given to the city during the Byzantine period. When active, the Basilica of St. John was the second-largest church in Anatolia.

The impressive ruins of the basilica are still visible. The basilica had a cross plan with six domes. Under the central dome was the sacred grave of St. John. Pilgrims have believed that a fine dust from his grave has magical and curative powers. In the apse of the central nave, beyond the transept, is the synthronon, semicircular rows of seats for the clergy. To the north, the transept was attached to the treasury, which was later converted into a chapel. The baptistery is from an earlier period and is now located north of the nave. Mosaics used by Byzantines are smaller than Roman mosaics, and examples can be noticed in the treasury.

The first of the Seven Churches of Revelation mentioned in the Book of Revelation is the Church of Ephesus. To this church, Jesus commended them for their endurance, their longsuffering, and dislike of false doctrine and evil behaviour. He chided them. However, Revelation 2.4 says, “…you have abandoned the love you had at first”. They no longer had the burning, consuming passion for their God they had when they were first saved and settled into the routine of the faith. He encourages them to find that fire again and continue where they were doing well.

Revelation 2:1-7 – Letter to the Church in Ephesus

Revelation 2:1-7

(1) “To the angel of the church in Ephesus write:

These are the words of him who holds the seven stars in his right hand and walks among the seven golden lampstands. (2) I know your deeds, your hard work and your perseverance. I know that you cannot tolerate wicked people, that you have tested those who claim to be apostles but are not and have found them false. (3) You have persevered and have endured hardships for my name and have not grown weary.

(4) Yet I hold this against you: You have forsaken the love you had at first. (5) Consider how far you have fallen! Repent and do the things you did at first. If you do not repent, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place. (6) But you have this in your favour: You hate the practices of the Nicolaitans, which I also hate.

(7) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches. To the one who is victorious, I will give the right to eat from the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Ephesus Ancient City“

The Church of Smyrna

Location: İzmir – distance from Çeşme 90km

Occupying the northern wing of the Agora of Smyrna and the site’s focal point, one of the Seven Churches of Revelation, the Basilica of Smyrna was three storeys high, including the basement floor. It had a rectangular plan and measured 161 by 29 metres. It is one of the largest basilicas ever built during the Roman period. The building has been used since the 2nd century B.C. as a Hellenistic period Stoa and at least the first quarter of the 2nd century A.D. as a Basilica.

It underwent significant rebuilding after an earthquake in 178 A.D and was in use until the 7th century, when it was abandoned with the rest of the Agora. The architects of the Agora Basilica of Smyrna used Hellenistic forms and ideas to construct an essentially Roman building with exceptional dimensions and quite peculiar construction techniques and decorations. They followed the centuries-old architectural traditions of Asia Minor, combining them with new ideas, and realized a Roman civil basilica of Helleno-Roman ideas and forms.

The remarkably well-preserved basement level of the Smyrna Basilica contains four galleries. The first and second galleries are on the south and are covered by 55 arches. Regular-shaped stone plaques are placed upon these arches, which are built of hewn stone. After the earthquake of 178 A.D. and to reinforce the upper stories, one out of every two arches in the first gallery was strengthened with square supports made of rubble and reused materials.

Among the interesting characteristics of the galleries are wall pictures and inscriptions, which represent almost every aspect of the daily life of the Roman period. They were made with incising techniques, painted lines, and decorative motifs worked into the plaster of partitioning walls and arches. These two galleries in the basement story bear traces of the North Stoa, located here in the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic plan and structural character of the building were passed onto the Roman period construction, and today, it can best be observed in the workmanship of the South Wall of the first gallery.

The lighting and ventilation of the basement of such a large structure must have been a problem. The rectangular windows on the first gallery’s south-facing wall were used from the Hellenistic period onward. In the courtyard, the windows opening onto the steps of the Basilica must have been intended to solve this problem. An effort was made to convey to the inner spaces the light and air from windows and doors serving the 1st and 4th galleries at points where these architectural solutions were insufficient; torches and lamps were used.

In the Book of Revelation, the second of the Seven Churches of Revelation, Smyrna, received words of comfort. They were mocked and persecuted for their faith, and it was going to get worse before it got better. It was not a wealthy church, with opportunities to flee and take refuge elsewhere. Some theologians believe many of the labourers of this church were expelled from their labour guilds – and unable to work in their craft legally – because of their conversion to Christianity.

Revelation 2:10 says, “Do not fear what you are about to suffer. Behold, the devil is about to throw some of you into prison, that you may be tested, and for ten days, you will have tribulation. Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life” Though they would suffer in this life, God had a reward for them.

Revelation 2:8-11 – Letter to the Church in Smyrna

Revelation 2:8-11

(8) “To the angel of the church in Smyrna write:

These are his words: who is the First and the Last, who died and came to life again. (9) I know your afflictions and poverty, yet you are rich! I know about the slander of those who say they are Jews and are not but are a synagogue of Satan. (10) Do not fear what you are about to suffer. I tell you, the devil will put some of you in prison to test you, and you will suffer persecution for ten days. Be faithful, even to the point of death, and I will give you life as your victor’s crown.

(11) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches. The victorious one will not be hurt at all by the second death.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Izmir Agora” (to be added)

The Church of Pergamon

Location: Bergama – distance from Çeşme 220km

The most famous structure in the Ancient City of Pergamon is the monumental altar, also called the Great Altar, which was probably dedicated to Zeus and Athena. The foundations are still located at the original site, but the remains of the Pergamon frieze, which originally decorated it, are displayed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Many scholars believe that the reference to Satan’s Throne in Revelation 2:13 refers to the great Pergamon Altar, given its resemblance to a gigantic throne.

The Red Basilica is a monumental ruined temple built over the River Selinus in the lower city of Pergamon at the foot of the hill, now part of Bergama’s commercial centre. The temple was built during the Roman Empire, probably during Emperor Hadrian’s time (76 – 138 A.D. Emporer 117 – 138 A.D.). It is one of the most significant Roman structures that still survives from ancient Greece.

The temple is thought to have originally been for worshipping Isis, Serapis, and other Egyptian gods. Although the building was enormous, it was only one part of a much larger sacred complex surrounded by high walls. Built directly over the river, a 196-metre bridge spanned two channels under the temple. The Pergamon Bridge remains today, supporting modern buildings and vehicle traffic.

At some point during the early Christian era, the temple was gutted by fire. It was not restored but was redeveloped in the 5th century A.D. as a Christian basilica dedicated to St. John, built inside the shell of the destroyed temple. Arcades were built, dividing the interior into a central nave and two side aisles. The eastern wall was demolished and replaced with an apse. The floor level was raised by about two metres, obscuring the original Roman floor, though archaeologists have since restored the former floor level.

The church was probably destroyed by Arab forces, who besieged and looted the city in 716–717 during their unsuccessful bid to conquer Constantinople. In 1336, Pergamon fell into Turkish hands, and the building was converted into a mosque. Today, the main temple ruins and one of the side rotundas can be visited, while the other rotunda is still being used as a small mosque.

According to the Book of Revelation, the third of the Seven Churches of Revelation, Pergamon was surrounded by wickedness in their city, but they held fast to their beliefs. Their location was so full of wickedness that in Revelation 2:13, the Bible calls it “…where Satan has his throne…the place where Satan dwells”. However, some church members still held onto their former traditions, unwilling to let go of their idols. Others indulged in false doctrine. Jesus calls on this church to stop these sins. They did receive consolation as well because many from this church had been martyred.

Revelation 2:12-17 – Letter to the Church in Pergamon

Revelation 2:12-17

(12) “To the angel of the church in Pergamon write:

These are the words of him who has the sharp, double-edged sword. (13) I know where you live—where Satan has his throne. Yet you remain true to my name. You did not renounce your faith in me, not even in the days of Antipas, my faithful witness, who was put to death in your city—where Satan dwells.

(14) Nevertheless, I have a few things against you: There are some among you who hold to the teaching of Balaam, who taught Balak to entice the Israelites to sin so that they ate food sacrificed to idols and committed sexual immorality. (15) Likewise, you also have those who hold to the teaching of the Nicolaitans. (16) Repent therefore! Otherwise, I will soon come to you and fight against them with the sword of my mouth.

(17) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches. To the victorious one, I will give some of the hidden manna. I will also give that person a white stone with a new name written on it, known only to the one who receives it.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Pergamon Ancient City“

The Church of Thyateira

Location: Akhisar – distance from Çeşme 200km

During the early Christian period, the church at Thyateira was fundamental as one of the most significant northern Aegean cities. Thyateira is referenced in Acts and Revelation as the centre of Lydia and later one of the main churches of Asia Minor (Acts 16:14; Revelation 2:18-29). Paul, who spent most of his three years in the Asian provinces in Ephesus, may have visited Thyateira and brought the Gospel there.

The Christian community thrived until the population exchange of 1923. Since then, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople has maintained an exarch based in London with the title Archbishop of Thyateira, responsible for the Greek Orthodox Church in Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islands. The Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain is based at Thyateira House in central London (W2), near Lancaster Gate.

The Book of Revelation says that Thyateira, the fourth of the Seven Churches of Revelation, had problems with false teachers. There was a woman in the church who claimed to be a prophetess, who committed sins of sexual immorality, and whose behaviour was reminiscent of Jezebel, Ahab’s wicked wife, whose story is told in the Old Testament (Book of Kings). Despite the church’s love, patience, and endurance, they tolerate this wicked woman taking an inappropriate role of leadership, giving false prophecies, and being flagrantly sinful.

In Revelation 2:21, God has given this woman and the church time to turn from this sin; “I have given her time to repent of her immorality, but she is unwilling.”. The message ends with encouragement for those who did not follow this prophetess.

Revelation 2:18-29 – Letter to the Church in Thyateira

Revelation 2:18-29

(18) “To the angel of the church in Thyateira write:

These are the words of the Son of God, whose eyes are like blazing fire and whose feet are like burnished bronze. (19) I know your deeds, love and faith, service and perseverance, and that you are now doing more than you did at first.

(20) Nevertheless, I have this against you: You tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet. By her teaching, she misleads my servants into sexual immorality and the eating of food sacrificed to idols. (21) I have given her time to repent of her immorality, but she is unwilling. (22) So I will cast her on a bed of suffering, and I will make those who commit adultery with her suffer intensely unless they repent of her ways. (23) I will strike her children dead. Then all the churches will know that I am he who searches hearts and minds, and I will repay each of you according to your deeds.

(24) Now I say to the rest of you in Thyateira, to you who do not hold to her teaching and have not learned Satan’s so-called deep secrets, ‘I will not impose any other burden on you, (25) except to hold on to what you have until I come.’

(26) To the one who is victorious and does my will to the end, I will give authority over the nations— (27) that one ‘will rule them with an iron sceptre and will dash them to pieces like pottery’—just as I have received authority from my Father. (28) I will also give that one the morning star. (29) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Thyateira Ancient City“

The Church of Sardis

Location: Sart – distance from Çeşme 185km

The citadel of Sardis was celebrated throughout history and was described by the Greek historian Polybius (c. 200-118 B.C.) as “the strongest place in the world”. In this era, the Greek language replaced the Lydian, and principal buildings were erected, including the massive Temple of Artemis, the fourth largest Iconic temple in the world, which is visible today.

In 129 B.C., Sardis passed to the Romans and prospered under the peace of the early Roman era. During the 4th century A.D., as the site of one of the Seven Churches of Revelation, it became an important Christian centre. By the close of the 6th century A.D., Sardis constituted a city with a prosperous heritage, the ancestral home of Lydians, the birthplace of coinage, the location of the Temple of Artemis, and a community that supported Jewish and Christian faiths.

The Temple of Artemis was most likely conceived and developed in the 3rd or 2nd century B.C. Sometime during the first half of the 2nd century A.D., the temple was incorporated into the Roman Imperial Cult. The gigantic structure was still unfinished by the end of the 4th century A.D. when it was abandoned with the coming of Christianity, and a small church was erected at the southeast corner. Dozens of crosses crudely carved on its marble walls testify to the attempt to regain the magnificent pagan structure for a new use.

The late Roman synagogue of Sardis is the largest known synagogue of the ancient world. The city’s churches included a 4th-century church outside the city walls, a chapel attached to the temple of Artemis, and a large basilica near the city’s centre. The Turkish government permitted international excavations to commence in 1910, during which the first of several Byzantine-style churches was discovered.

The substantial 3rd-century A.D. Sardis Synagogue, built by Jewish merchants, featured a large central hall with rows of columns and ornate decorations, including elaborate mosaics and frescoes. Intricate carvings and inscriptions in Hebrew and Aramaic adorn the walls. At the time of construction, the Jewish community was experiencing significant upheaval and was transitioning from temples to synagogues.

The earliest extant Christian church at Sardis is a small, 4th-century mortuary chapel known as Church M. It was built on the abandoned grounds of the Hellenistic Greek Temple of Artemis on the Acropolis and discovered in the early 1900s by a professor at Princeton on the First Sardis Expedition.

The construction of Church M within the site of the Temple of Artemis reveals the extensive transformation sweeping across the Roman empire throughout the 4th century. Official recognition of Christianity by Constantine the Great (272-337 A.D., reign 306-337 A.D.) soon heralded his establishment of the new eastern capital at Constantinople. Though the temple was probably inactive by this time, its enormous walls and magnificent columns continued overshadowing the area.

Engraved crosses and religious graffiti still visible near the temple’s east entrance reveal the exertions of local inhabitants to deconsecrate the structure and nullify any remaining spiritual power of the classical cult. Church M may have been purposed both for worshipful use by local inhabitants and to honour this significant change in Lydian religious traditions.

On the hillside of the road that leads to the Temple of Artemis is a partially excavated simple aisled basilica known as Church EA. The church’s proximity to the southwest walls of Sardis indicates an effort at urban expansion by creating a Christian quarter outside the defences. Identification of coins unearthed during excavation suggests it may have been built in the middle of the 4th century A.D., nearly a century before the first Christian building of its kind was erected in Constantinople.

In the north aisle, a vast and richly coloured mosaic floor was uncovered with geometric shapes composed of small irregularly cut tiles, and evidence of painted walls of rich blues and black exists in over 400 fragments of brick and plaster. Until the 7th century A.D., the church added an east building and west wing, a large square atrium, a north courtyard, and numerous architectural carvings. Subsequent additions and repairs throughout the medieval period indicate that the building remained active until as late as the 13th century, when a small, multi-dome church (also known as Church E) with ornate exterior decoration was built over it.

According to the Book of Revelation, Sardis, the fifth of the Seven Churches of Revelation, was a seemingly active church that was full of good works. Sardis was also a city of wealth, known for the carpet industry and minting coins. However, this church’s wealth and good works meant nothing because the church was spiritually dead. They epitomized a church that seemed good, but many had cold hearts toward the Lord. They most likely put their faith in their works, pridefully assuming they were saved or in good standing with the Lord.

The message of Revelation 3:2 is, “Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God”. The church was not beyond hope, but needed to find that passion for Christ again.

Revelation 3:1-6 – Letter to the Church in Sardis

Revelation 3:1-6

(1) “To the angel of the church in Sardis write:

These are the words of him who holds the seven spirits of God and the seven stars. I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. (2) Wake up! Strengthen what remains and is about to die, for I have found your deeds unfinished in the sight of my God. (3) Remember, therefore, what you have received and heard; hold it fast, and repent. But if you do not wake up, I will come like a thief, and you will not know when I will come to you.

(4) Yet you have a few people in Sardis who have not soiled their clothes. They will walk with me, dressed in white, for they are worthy. (5) The victorious one will, like them, be dressed in white. I will never blot out the name of that person from the book of life but will acknowledge that name before my Father and his angels. (6) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Sardis Ancient City“

The Church of Philadelphia

Location: Alaşehir – distance from Çeşme 235km

The Church of St. Ioannes has been in the city since the Early Byzantine Period (6th century). Located almost in the centre of the city walls, the Church of St. Ioannes is the only surviving church within the ancient city. Today, it is called “Üçayak” or “the Church of St. John” (of St. John the Apostle); its original name is uncertain.

Travellers’ accounts show almost all of the church was already ruined by the early 19th century, with only its four partly standing piers from which the remains of brick arches rise, part of a wall of the choir, and some damaged frescoes surviving and today the site of the church functions as an open-air museum with the four piers, one of which is preserved only to ground level, and several artefacts brought from neighbouring Alaşehir. As only the four piers of the building exist, most suggestions can not go beyond speculation until a thorough excavation has been conducted. The pillars’ height, thickness and connection to the arches give the impression that it was once a magnificent structure.

The best-preserved pier is located in the northeast. It is about 14.5 metres high, with the brick vault fragments surmounting it. All its faces are made of ashlar masonry, while the north and east faces are damaged and subsequently partly restored. The stone string course is at the top of the pier, only on the south and west sides. In plan, the pier has straight edges on the north and east, while on the south and west, it has profiles with re-entrant angles indicative of the surmounting arches.

Today, among the vault fragments, one can trace the springing of the arches on the west and south, a pendentive fragment at the southwest corner, and the facades articulated by blind arches recessed twice on the north and east with saw-tooth brick ornament. Unfortunately, the frescoes retained today lack complete stylistic features or identifiable narrative scenes. Only a few of those which once adorned the surfaces of the south and west sides of the northeast pier are partly recognizable today. Among them are probable busts of saints with halos, some of whom also appear to have epitrachelions with crosses and Bibles inside a row of roundels immediately below the string course on the south side of the northeast pier.

In the Book of Revelation, the sixth of the Seven Churches of Revelation, Philadelphia receives encouragement and affirmation in its message. Despite poverty and hardship, they stayed faithful to God. Revelation 3:8 says, “I know your deeds. See, I have placed before you an open door that no one can shut. I know that you have little strength, yet you have kept my word and have not denied my name.”. Jesus wanted this body of believers to continue as they were. They would spend eternity in Heaven with Him.

Revelation 3:7-13 – Letter to the Church in Philadelphia

Revelation 3:7-13

(7) “To the angel of the church in Philadelphia write:

These are the words of him who is holy and true, who holds the key of David. What he opens, no one can shut, and what he shuts, no one can open. (8) I know your deeds. See, I have placed before you an open door that no one can shut. I know that you have little strength, yet you have kept my word and have not denied my name. (9) I will make those who are of the synagogue of Satan, who claim to be Jews though they are not, but are liars—I will make them come and fall down at your feet and acknowledge that I have loved you. (10) Since you have kept my command to endure patiently, I will also keep you from the hour of trial that is going to come on the whole world to test the inhabitants of the earth.

(11) I am coming soon. Hold on to what you have so that no one will take your crown. (12) The one who is victorious I will make a pillar in the temple of my God. Never again will they leave it. I will write on them the name of my God and the name of the city of my God, the new Jerusalem, which is coming down out of heaven from my God; and I will also write on them my new name. (13) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches.

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Philadelphia Ancient City“

The Church of Laodicea

Location: Goncalı – distance from Çeşme 325km

The recently restored Laodicean Church is now a main tourist attraction in Laodicea. Discovered and completely unearthed in 2010, it is one of the oldest Christian churches in the world, dating back to the reign of Constantine the Great (272 -337 A.D., Emperor 306 – 337 A.D.). Severely damaged by an earthquake in 494 A.D., it was rebuilt and finally destroyed in an earthquake circa 602 – 610 A.D. Now covered with a protective roof, a partly transparent platform has been prepared for the visitors to view below. The three-aisled basilica has eleven semicircular apses, two entrances, and a floor decorated with many mosaics. The church walls were decorated with frescoes and marble slabs.

Finally, in the Book of Revelation, John addresses the last of the Seven Churches of Revelation, the Church of Laodicea. While the other churches received some encouragement or commendation from the Lord, this church received no positive words. Like Sardis, Laodicea had abundant resources but held an indifferent spirit – described as lukewarm – toward the Lord. He wants them to grow hot or cold toward him but not to remain lacking in any passion toward the faith. While they were doing well in an earthly fashion, they were spiritually lacking. Here, Jesus asks for them to let Him in.

Revelation 3:20 says, “Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me.”. Despite their lack of spirituality, Christ waits expectantly for them to open their hearts to Him.

Revelation 3:14-22 – Letter to the Church in Laodicea

Revelation 3:14-22

(14) “To the angel of the church in Laodicea write:

These are the words of the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the ruler of God’s creation. (15) I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either one or the other! (16) So, because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth. (17) You say, ‘I am rich; I have acquired wealth and do not need a thing.’ But you do not realize that you are wretched, pitiful, poor, blind and naked. (18) I counsel you to buy from me gold refined in the fire, so you can become rich; and white clothes to wear, so you can cover your shameful nakedness; and salve to put on your eyes, so you can see.

(19) Those whom I love I rebuke and discipline. So be earnest and repent. (20) Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me.

(21) To the victorious one, I will give the right to sit with me on my throne, just as I was victorious and sat down with my Father on his throne. (22) Whoever has ears, let them hear what the Spirit says to the churches.”

Source: Biblegateway.com

See also on LikeCesme.com “Laodicea Ancient City“

The Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament; its title comes from the first word of the text: apokalypsis (ἀποκάλυψις), meaning ‘revelation’ in Hellenistic Greek (Koine Greek), an unveiling or unfolding of things not previously known. The Book of Revelation is the only apocalyptic book in the New Testament. It occupies a principal place in Christian theology, concerned with death, judgement, and the final destiny of the soul and humankind.

The author of the book, John, makes it clear that the Book of Revelation is both an “apocalypse” (revelation) and a “prophecy.” This type of Jewish literature recounted a prophet’s symbolic visions that revealed God’s heavenly perspective on history so that the present could be viewed considering history’s final outcome. It was meant to comfort and/or challenge God’s people.

John says he was exiled to the island of Patmos, where he saw a vision of the risen Jesus standing among seven burning lights. The image, adapted from Zechariah 4, symbolises seven churches in Asia Minor. Jesus addressed the specific problems facing each church and warned them that a “tribulation” was upon the churches that would force them to choose between compromise and faithfulness. Amid persecution, Jesus calls the churches to faithfulness.

The precise identity of John remains a point of academic debate. Second-century Christian writers identify John the Apostle as the “John” of Revelation. Modern theological scholars consider that nothing can be known about him except that he was a Christian prophet and characterise him as “John of Patmos”.

Seven Churches of Revelation Guided Tours

For guided tours of the Seven Churches of Revelation, see links below: