Aphrodisias is located in the fertile valley formed by the Morsynus River in the ancient region of Caria. The site consists of two sections, encompassing the archaeological site of Aphrodisias, following the walls that encircle the city and the marble quarries located to the northeast. The temple of Aphrodite dates from the 3rd century B.C. and the city was built one century later and had a population of approximately 10,000 citizens. The wealth of Aphrodisias came from the marble quarries and the art produced by its sculptors. The city streets are arranged around several large civic structures, which include temples, a theatre, an agora and two bath complexes.

Getting there: 290km southeast of Çeşme in the province of Aydın via the E87 highway, close to the new village of Geyre. 3 hours and 25-minute drive by car İzmir-Aydın-Nazilli-Kuyucak-Başaran-Geyre.

Map location & entry: Geyre, 09385 Karacasu/Aydın – Open daily 08:30-17:30 (1 Oct- 1 Apr) 08:30-19:00 (1 Apr – 1 Oct) – Ticket price approx €12.00.

Aphrodisias Ancient City – Table of Contents

Aphrodisias Today

The Ancient City of Aphrodisias had a cosmopolitan social structure (Greek, Roman, Carian, pagan, Jewish, Christian) abundantly articulated in the site’s 2,000 surviving inscriptions. The site covers 152 hectares and was registered on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2017. The registration criterion includes: (ii) The exceptional production of sculpted marble blends local, Greek, and Roman traditions, themes and iconography. It is visible throughout the city in an impressive variety of forms, from large decorated architectural blocks to larger-than-life-size statues to small portable votive figures. (iii) Aphrodisias occupies a pre-eminent place in the study of sculpture in the Roman world. Its quarries and its sculpture workshops made it a major art centre, famous for the creativity and technical skill of its sculptors, having one of the very few known and systematically excavated sculpture workshops of the Roman Empire, which provides a fuller understanding of the production of marble sculpture than anywhere else in the Roman world. (iv): An exceptional example of the built environment of a Greco-Roman city in inland Asia Minor. (vi): It was famous in antiquity as the cult centre of a version of Aphrodite, which amalgamates aspects of an archaic Anatolian fertility goddess with those of the Hellenic goddess of love and beauty.

Brief History of Afrodisias

Aphrodisias was founded as a city-state in the early 2nd century B.C. It is set out in a grid of streets with only a few structures unaligned, such as the temple of the goddess Aphrodite. The city shared a close interest in the goddess Aphrodite with Roman dictator Sulla (138-78 B.C), Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.), and the emperor Augustus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.) and had a close relationship with Rome. It obtained a privileged ‘tax-free’ political status from the Roman senate and developed a solid artistic and sculptural tradition during the Imperial Period. Many elaborately decorated structures were erected during Roman rule, all made from the local marble.

The sanctuary at Aphrodisias had a distinctive cult statue of Aphrodite, which defined the city’s identity. The Aphrodite of Aphrodisias combined aspects of a local Anatolian, archaic fertility goddess with those of the Hellenic Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty. This identifying image has been found in Anatolia across the Mediterranean, from Rome to the Levant. The importance of the Aphrodite of Aphrodisias continued well beyond the official imperial acceptance of Christianity; the Temple did not become a church until circa A.D. 500.

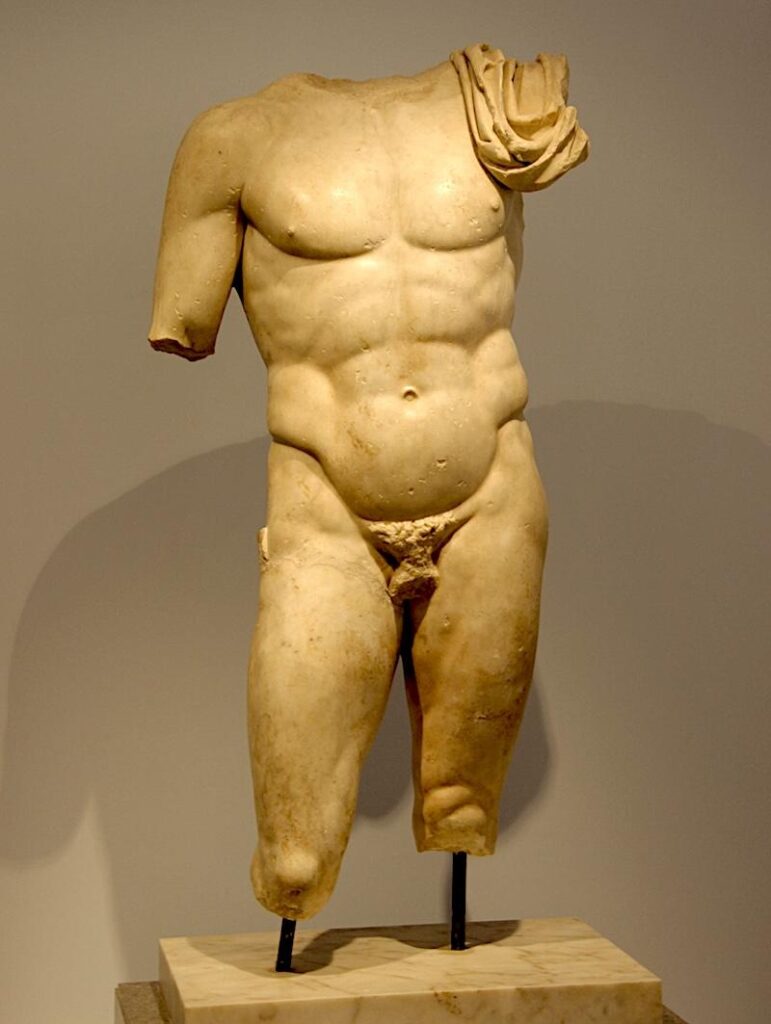

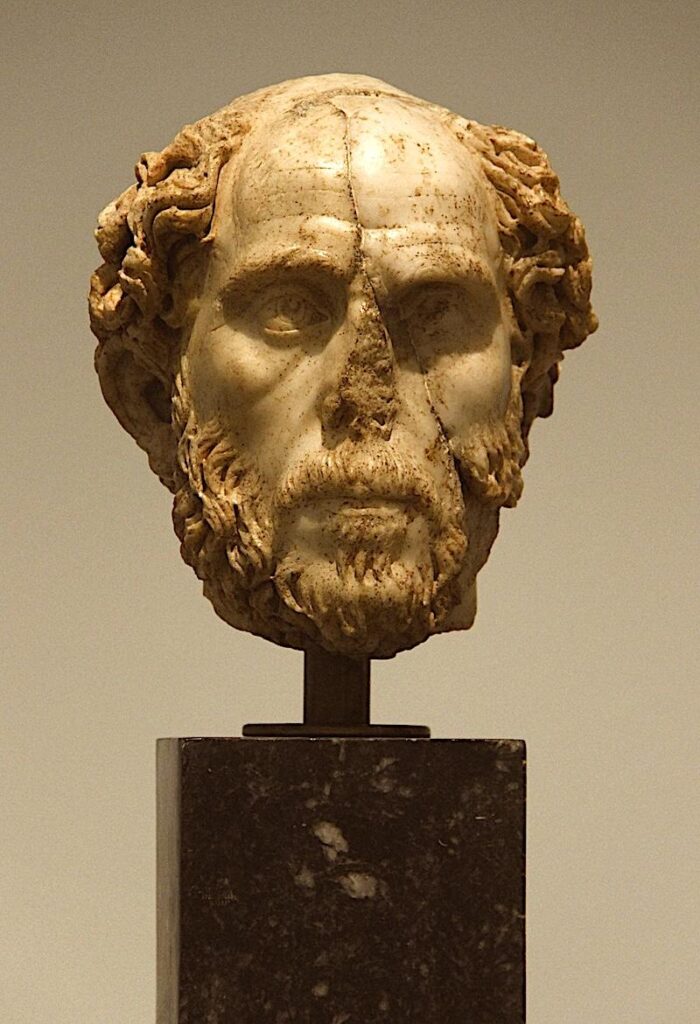

The proximity of the marble quarries to the city was a significant reason that Aphrodisias became an outstanding, high-quality production centre for marble sculpture. Sculptors from the city were famous throughout the Roman Empire. They were well-known for virtuoso portrait sculpture and Hellenistic-style statues of gods and Dionysian figures. In late antiquity (4th-6th centuries A.D.), Aphrodisian sculptors were in great demand for marble portrait busts and statues of emperors, governors and philosophers in the major centres of the empire, including Sardis, Stratonikeia, Laodikeia, Constantinople and Rome.

Afrodisias Museum

The artefacts from the excavations of Afrodisias are today exhibited at the Afrodisias Museum at the ancient city’s entrance on the archaeological site. The richest collection in the museum consists of sarcophagi, with statues and reliefs from the Aphrodisias sculpture school, which lasted from the late Hellenistic to the early Byzantine period.

In 1947, the General Directorate of Monuments and Museums converted the caravanserai in the old Geyre Village within this settlement area into a museum warehouse to safeguard the finds discovered at the Aphrodisias site. The existing museum building was opened in 1979, displaying the Roman, Byzantine and Early Islamic Era artefacts found during the excavations of Aphrodisias Ancient City. In the Small Artefacts Exhibition Hall are also prehistoric artefacts of late Neolithic early Chalcolithic (early, middle and late) Bronze Ages, discovered during excavations carried out Acropolis Hil and Pekmez Tepe Mound located within the archaeological site and Lydian ceramics obtained from the mounds and surrounding area of Aphrodite Temple, Archaic, Classic, Hellenistic Era Artifacts as well as artefacts discovered during the excavations carried out in the archaeological site, were displayed.

The Temple of Aphrodite

The conversion of the Temple of Aphrodite into a cathedral around 500 A.D. is unique among temple-to-church conversions in its engineering and transformative effect. Today’s remnants of the Temple of Aphrodite are mainly the Basilica (Cathedral of St. Michael), into which it was converted.

Built entirely of marble, the sanctuary of Aphrodite was an Ionic temple surrounded by columns. It was the house of the goddess Aphrodite, containing her cult statue. A vast colonnade surrounded the temple chamber; it has an eight-column facade, and its columns are set close together. The length had thirteen columns; its outer dimensions were 8.5 metres x 31 metres. The temple was constructed in phases starting circa 30 B.C. with the chamber and columned porch. The outer columns were added in the first century A.D., and in the second century A.D., the temple was enclosed by the elaborate collonaded court, with a two-storeyed columnar façade on the east side and by porticos on the other three sides.

The temple was converted into a church in the middle/late fifth century A.D. The Cathedral of St. Michael was considerably larger than the temple at 28 metres x 60 metres. The Cathedral remained in use until it was destroyed and burned in the early 1190s by Theodore Mankaphas from Philadelphia, who assumed the title of Byzantine emperor twice. The Temple/Basilica is a well-preserved monument that has been standing in its present state since that misfortune. The burning of roof timbers in the intense fire fractured the columns of the nave, but they remained standing.

Stadium

Constructed in the late first century A.D., the Stadium was carefully planned as an integral part of the city and had an unusual architectural form with two closed curved ends, known as “amphitheatral.” It is one of the largest and best-preserved examples of this stadium type in the ancient world. The 270-metre x 60-metre stadium had 30 rows of marble seats and a capacity of up to 30,000 people. The long sides are slightly elliptical.

Spectators entered the stadium by monumental stairways on the south side, facing the town; these stairs aligned with north-south streets in the city grid. Competitors entered through tunnels under the seating on both short ends. The Stadium staged traditional Greek athletic contests, such as foot races, long jump, wrestling, discus, and javelin throwing. It was also used for gladiatorial combats and wild-beast fights that were part of the regular programme of festivals held in honour of the Roman emperors. In late antiquity, when the traditional Greek games and naked athletics had declined in importance, the east end of the building was turned into an amphitheatre and arena designed explicitly for Roman-style entertainment.

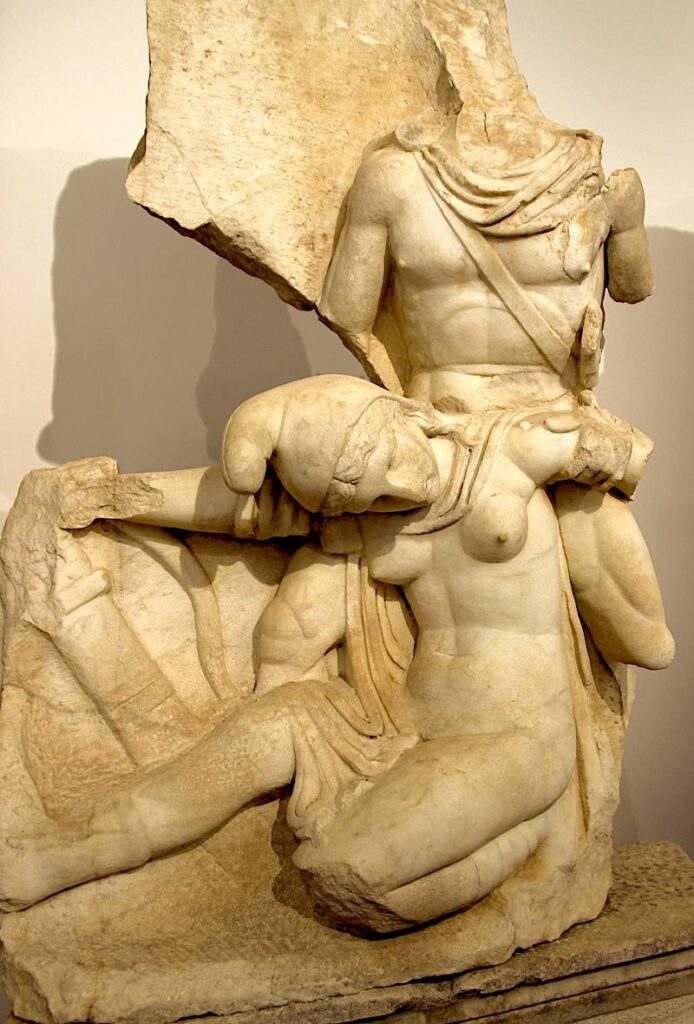

The Sebasteion

The Sebasteion is an elaborate cult complex where Augustus and the Julio-Claudian emperors were worshipped, representing a distinctive integration of Hellenistic, Roman, and Aphrodisian artistic traditions. The grandiose temple complex was constructed circa 20-60 A.D. during the reign of Tiberius and Nero. It consisted of a Corinthian temple and a narrow processional, a 90-metre avenue that was 14 metres wide and flanked by two portico-like buildings, each three-storeyed (12-metre high), with Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders.

The north and south buildings, which defined the processional avenue, carried marble reliefs in their upper two storeys for their entire length. The columnar architecture framed the reliefs so the two facades looked like closed picture walls. Some 200 reliefs were required for the whole project, and more than 80 were recovered in the excavation in 1979-1981. They featured Roman emperors, Greek myths, and a series of representative peoples of Augustus’ world empire, from the Ethiopians of eastern Africa to the Callaeci of western Spain. The Sebasteion reliefs are housed in a hall in the Aphrodisias Museum. Eighty per cent of the southern building reliefs of emperors and heroes have survived, while the northern building reliefs of peoples of empire are the least well-preserved of the complex.

The Agora

The Agora was the main civic square of the city and was one of the first components of the late Hellenistic city plan to be built in a marble architectural style. It was an enclosed space of approximately 202 metres x 72 metres, surrounded by Ionic porticos on all sides. An inscription from the double north colonnade records its dedication circa 30 – 20 B.C. to Gaius Julius Zoilos, a former slave who was born in Aphrodisias and, after being freed, amassed a large fortune that he later used to benefit his hometown. The south colonnade of the Agora was added later under Emperor Tiberius (42 B.C. – 37 A.D. Emporer 14 – 37 A.D.), to whom it was dedicated. This double colonnade was built in a single unit, back to back, with the Ionic colonnade on the north side of the Urban Park. The Agora was laid out with the Bouleuterion on its central axis.

The Theatre

The Theatre features an early example of a stage building with an aediculated façade (pulvinated/convex frieze with triangular pediment). The Aphrodisias theatre, which originally seated 7,000, preserves its full twenty-seven tiers of seats below the diazoma (walkway that separated the upper and lower seating) and a few rows of seats above it, as well as much of the stage architecture. The original seating was built against the hill in the late Hellenistic period. Sometime before 28 B.C., an elaborate three-storeyed marble stage building was commissioned by the former slave Gaius Julius Zoilos, as well as all the ornaments.

Excavations discovered several important statues on the stage and in the orchestra area. In the first century A.D., the theatre was extended upwards, and the seating was covered with marble. The “Archive Wall” in the theatre is a well-preserved collection of official imperial documents regarding the city’s status under the Empire inscribed on the north end wall of the stage building in the second and third centuries A.D.

On the north side, the retaining wall dropped to a lower level, where it shaped the back wall and portico of the Urban Park, which was accessed by a large and vaulted stairway through the retaining wall to the theatre above. In the second century A.D., the orchestra level in the Theatre was lowered to form a safe arena-pit for gladiatorial and animal shows. In the seventh century A.D., an immense wall of re-used material was built along the line of the back of the stage, blocking the entrances; the wall continued around the whole Theatre, turning it into a Byzantine fortification.

The Tetrastoon

The Tetrastoon or Four Porticoes is the marble-paved and collonaded square in front of the Theatre, built in the first or second century A.D. and restored to its current form circa 360-364 A.D. by Antonius Tatianus, a provincial governor. Adjacent to the theatre on the west side of the square was a place of honour for statues of emperors and governors. Two of these statues survive, one for Theodosius I or II, emperors from 369-395 and 402-450, respectively, and one for Governor Flavius Palmatus circa 500 A.D.

The Theatre Baths

Southeast of the Theatre and south of the Tetrastoon are the public baths, which are today identified as the Theatre Baths. They include a square caldarium (hot room) with a domed roof, a large, vaulted hall, probably the frigidarium (cold room), and a multi-purpose hall with two ornately carved piers from the mid-second century A.D.

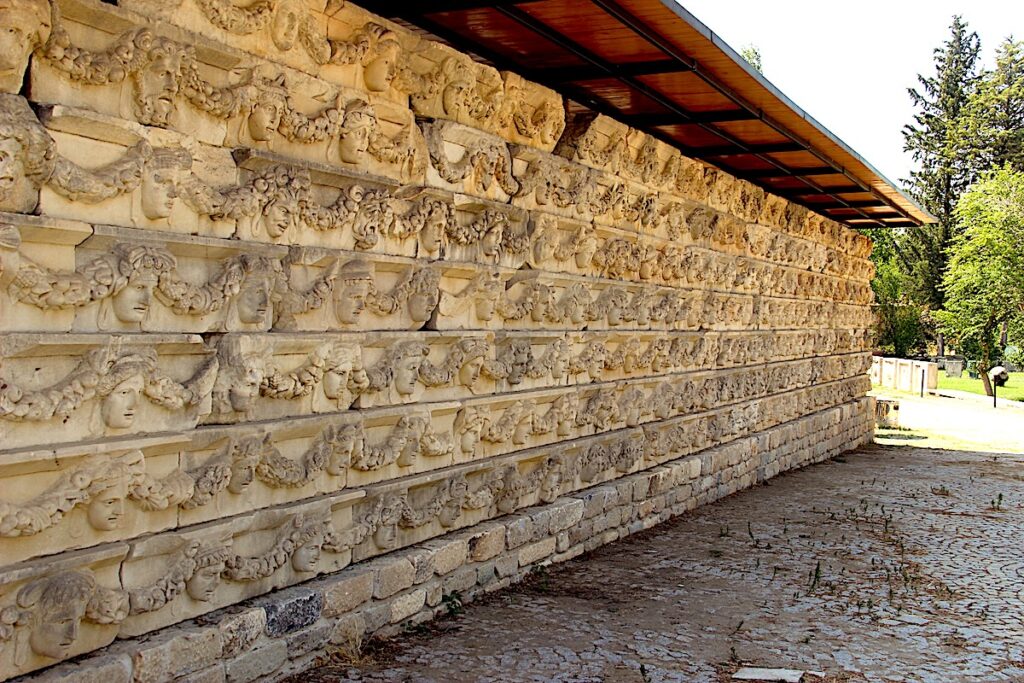

The Urban Park

Dedicated to Emperor Tiberius (42 B.C. – 37 A.D. Emporer 14 – 37 A.D.), the Urban Park parallel to the south of the Agora was the second public square of the city, a 215 metre by 70 metre colonnaded quadrangle. The north portico walkway frieze dividing the Agora was carved with motifs of fruit garlands draped over various masks.

The 20-metre-high masonry retaining wall of the Theatre sits to the southeast end of the park, while the Temple/Basilica closes the southwest corner, and the Hadrianic Baths to the west are behind a colonnade built in the early second century A.D. The large columnar facade, the Propylon of Diogenes, built in the first century A.D., enclosed the east side. Tunnels under the towers of the propylon gave access to the park from Tetrapylon Street. The spectacular 170 metre x 30 metre pool, which forms the centre of the piazza, was excavated in the 1980s. The water basin was bordered by palm trees, evidenced by a poem inscribed on the Propylon of Diogenes describing the “place of palms” and planting trenches uncovered in the excavation.

The Hadrianic Baths

Dedicated to Emperor Hadrian (76 – 138 A.D. Emporer 117 – 138 A.D.), the Hadrianic Baths were built in the early second century A.D. and connected with the west side of the Urban Park. They are a succession of barrel-vaulted bathing chambers and a sizeable collonaded forecourt with impressive marble architecture. The vaulted chambers were built of massive limestone blocks faced with marble, and the raised floors and pools were lined with marble. Constantly renovated and upgraded, they still functioned as baths into the sixth century A.D.

The Bouleuterion

The Bouleuterion (Council House) was the centre of political power in the city. It was an elaborate roofed structure built in the late second century A.D. by the family of Tiberius Claudius Attalos, a Roman senator and his brother Diogenes. Their statues dominated both the interior and the exterior. The building was a covered, theatre-like structure, lined with marble seating for a maximum of about 1,700 persons, with a two-storey columnar marble stage façade. This façade faced the auditorium and carried statues of important civic benefactors between its columns. The lower nine rows of the seating survive in exceptional condition; of the upper part, a further twelve rows, only the walls for the supporting vaults remain.

The Bouleuterion was large enough to serve various other purposes and entertainments, such as music and oratory performances, as well as for meetings of the Council. The building remained in use into late antiquity when its interior was remodelled by removing the roof and two to three rows of seats and creating a sunken orchestra, probably for wrestling contests. The re-modelling to a palaestra (wrestling school) is noted in a fifth-century A.D. inscription on the upper moulding of the stage. The statues of the two brothers stood on the ends of the walls that supported the seating and thus framed and dominated the stage. Statues and bases survive virtually complete of their father, Dometeinos, and his niece Tatiana. They stood outside, looking towards the Agora to which the Council House was connected and framing the entrances. Eight of the statues from the stage façade inside the building also survive.

The Tetrapylon

The Tetrapylon, the richly ornamented entrance to the outer Sanctuary of Aphrodite, is preserved with its elaborate and exquisitely carved architectural ornament. Erected in the mid/late second century A.D., it has sixteen columns (4 X 4) that support elaborate pediments on each side. Entering from the east side, along Terapylon Street, a major north-south street, visitors passed through the gate into a large open forecourt before the main sanctuary. From the inside at the west façade of the gate, the visitor would see an even richer elaboration of the architecture that marked this as the interior. The broken-recessed west pediment is decorated with high-quality relief work of Erotes hunting in acanthus foliage and deeply carved architectural ornament in an encrusted imperial style representing majesty and grandeur. A figure of Aphrodite framed in the central lunette was erased in the Christian period and replaced with a crudely engraved cross. A complete stone-for-stone reconstruction of the structure, using 85% original blocks, was completed in 1991.

The Propylon of Diogenes

Built by Diogenes the Younger, son of Menandros, at the end of the first century A.D., the Propylon of Diogenes was a colossal columnar façade that closed the urban park’s east end. The structure consisted of an eight-bayed, two-storeyed columnar scaenae frons (stage front) framed by two pyrgoi (towers), beneath which ran barrel-vaulted entrance tunnels. This façade accumulated a great display of portrait statuary representing emperors and local benefactors. A deep basin or nymphaeum was constructed before the façade in the sixth century A.D. from re-used material, including a series of balustrade reliefs with mythological subjects taken from an unknown second-century building.

The City Walls

The city wall is approximately 3.5 km long and is extensive, well-preserved, and precisely dated. Enclosing an area of about 72 hectares, it was at least 10.0 metres high and 2.5-3.5 metres wide. Inscriptions from circa 350-360 A.D. on two of the gates name the governors who paid for their construction. Before the wall construction, the city appeared to have been entirely unfortified, and this would have radically changed both the image of the city and the direction of traffic in and out of town through the seven known gates. The interior face of the wall is built of regularly coursed, mortared, sub-ashlar masonry, while the exterior face consists almost entirely of large re-used marble blocks, carefully arranged to give the appearance of a megalithic marble wall, most of which would be re-used blocks from monumental tombs near which the wall passed.

Ancient Marble Quarry

The Ancient marble quarry is located 3km north of the museum along the minor road directly across the D585 leading towards the village of Palamutçuk. The proximity of the marble quarries to the city was a significant reason that Aphrodisias became an outstanding high-quality production centre for marble sculpture and developed sculptors who were famous throughout the Roman Empire. The quarries covered an area of about 3-4 square kilometres and were sufficient to provide the needs of the city for its building, but not of a scale to support wide export of marble as a raw material, except long-distance export of expensive, finished products, and regional export of some larger statues and sarcophagi. It was first exploited in the late hellenistic period by ad hoc surface quarrying, the main quarries were opened in the early and high Roman Imperial period, but some remained active into the late antique period.

Social Media & Information Links

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture & Tourism – Aphrodisias Museum English Website (includes a link to their .pdf brochure)

Aphrodisias Excavations Project – Collaboration of New York University, Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture & Tourism, and University of Oxford – English Website

UNESCO World Heritage Convention List – No. 1519 – Aphrodisias – Criterion for Aphrodisias Listing English Website

Turkish Archeaoligal News – Aphrodisias Museum – English Article (Nov 2023) on Museum Artefacts